|

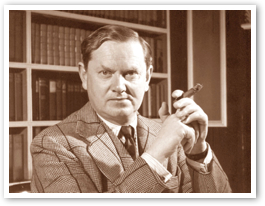

| Portrait of the Artist as a Bright Young Thing |

But it does have everything to do with a man who during his life and after his death on Easter Sunday (April 10) 1966 was often acclaimed the greatest Catholic novelist of the 20th century--and more widely acclaimed, even by people who didn't like him, as having been one of the funniest novelists and greatest literary craftsmen of the last century as well. On those terms alone he deserves continued attention--or fresh discovery by those who have not yet had the joy of reading a wonderful writer. He is, in sum, a delightfully droll antidote to and distraction from the woes of the world today, not least the endless ghastly pageant that is modern politics, which he loathed (as we shall see below).

|

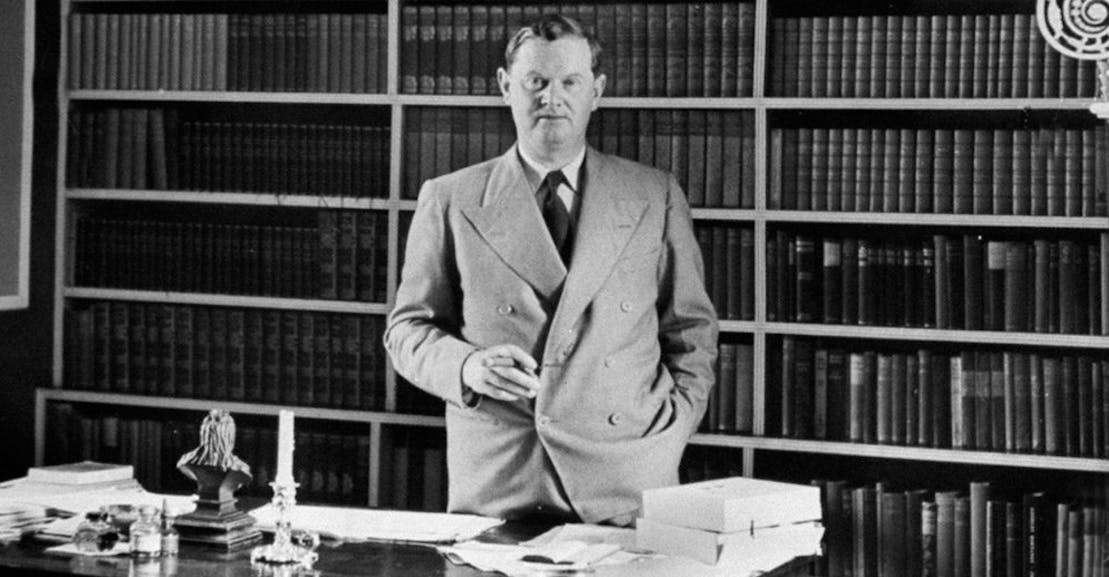

| The Artist's Famously Terrifying 1000-Yard Stare |

Indulging this jejune pastime farther afield, I published articles in Canada and the United States, and gave lectures in both countries as well as Ukraine, about Waugh, deliberately using provocative titles (e.g., “In Defense of Christian Snobbery,” some excerpts of which and commentary on which may be found here) and highlighting choice bits from his rich correspondence and diaries as well as his novels and short stories. One in particular has often come in handy over the years as we are assaulted with fad diets and hectoring health nazis: "Food can and should be a source of delight. As for 'nutrition'--that is all balls."

More recently, I gave a scholarly lecture at a literary conference examining some of Waugh's characters and asking whether they could be considered examples of "holy fools" or iurodivy. My article was later published in Unruly Catholics, a book I first detailed here.

Now, a half-century after his early but--for him--welcome death (his letters and diaries for much of the last decade of his life indicate clearly how he welcomed the prospect of death), let us look back at both what he wrote, and what has been written about him.

To start with the latter category first: Biographies. There are four major biographies that have been written about him. All are interesting, and each contributes something unique, partly because each is written from a very different perspective. To take the weakest first, we start with Martin Stannard's two-volume Evelyn Waugh: The Early Years 1903-1939. The first is somewhat the more problematic of Stannard's two volumes, indulging as it does--though less so in the second volume, Evelyn Waugh: The Later Years 1939-1966--in subjecting Waugh to a crude kind of hostile armchair psychoanalysis.

The second biography was actually the first to appear within a decade after Waugh's death in April 1966, and it was written by his friend and sometime traveling companion Christopher Sykes, Evelyn Waugh: A Biography (1975). This did not pretend to be anything like a comprehensive and totally objective biography. The author was a sometime friend of Waugh, but had nonetheless enough distance to write a fair study of the man without indulging in any kind of romantic hagiography.

The third biography that came out was very good, and when it was published in 1994 was to that point the most comprehensive study extant: Selina Hastings, Evelyn Waugh: A Biography (1994). It was a literary study, and quite good, but it left one large lacuna: Waugh's faith, which Hastings, to her credit, seems to have felt unqualified to address and so she commendably passed over it largely in silence rather than make a hash of it, as Stannard did and others did during Waugh's life and since his death.

But far and away the best biography of Waugh, which has never been surpassed, was and is the absolutely splendid and superlative Douglas Lane Patey, The Life of Evelyn Waugh: A Critical Biography (1998). Patey's study is a true monument to the art of scholarly biography. I have often returned to it not only because it is such a delightful book, but also because it is a model of how to write a scholarly biography with great lucidity, intelligence, insight, and grace. Alone of the four biographies Patey's is not only the most penetrating and comprehensive, but also the only theologically literate study of Waugh's mid-century Catholic worldview. It is Patey's very considerable achievement that he could describe Waugh's faith accurately and without the rancor of a Martin Stannard, the dry dismissiveness of Sykes in some places, or the near-total silence of Hastings. Patey really makes it clear that Waugh cannot be understood without understanding his Catholic Christian faith. If you read only one biography, this is the one to read, and indeed the only one you really need unless you want to study the man as obsessively as I have. (It seems, in October of this year, we are to have a fifth biography: Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited. I look forward to reading it when it appears.)

Memoirs, Diaries, and Letters:

But there are other semi-biographical books or personal memoirs treating Waugh in whole or in part, most of them written by some of his friends. Frances Donaldson was Waugh's neighbor in the last decade of his life, and her short book offers some lovely and hilarious anecdotes about him: Evelyn Waugh: Portrait of a Country Neighbor.

A similar study of Waugh at one brief period of his life may be found in W.F. Deedes, At War with Waugh: the Real Story of Scoop. This is a very narrowly and very modestly interesting study of interest only to die-hard Waugh fanatics.

At points, Waugh was friends with nearly all the celebrated Mitford sisters, and insights into his friendship with Nancy Mitford, an accomplished novelist in her own right, may be found in The Letters of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh.

In a similar vein, one should also see Mr. Wu and Mrs.Stitch: The Letters of Evelyn Waugh and Diana Cooper, 1932-66. This collection of letters is perhaps especially useful in dispelling the notion that Waugh was always a cranky and rude old man, even with his friends. We see a tender side to him in, e.g., consoling Diana after the death of her husband, and constantly extending invitations to her to visit afterwards. When he indulges in some rather rough and ready Catholic apologetics with her, she rebukes him and he straightaway apologizes with complete grace and sincerity, thereby putting another lie about him to rest.

But perhaps the most diverse collection of remembrances was edited by David Pryce-Jones, Evelyn Waugh and His World. Containing, inter alia, essays by the priest who received Waugh into the Church in 1930, and his comrades in arms in Yugoslavia in the early 1940s, it offers many fascinating glimpses into various aspects of Waugh's life, as well as one of the most generous samplings of photographs and reproductions of Waugh's sketches for many of his novels. (Waugh had tremendous respect for the crafts, and for craftsmanship--sketching, painting, sculpting, and furniture-making. Indeed, he himself thought about furniture making as a career at one point, and his last son, Septimus Waugh, has long had a career as a cabinet-maker, joiner, and carver--as well as dabbling in the "family business" of writing.)

Going beyond piecemeal correspondence, the largest single collection of letters is very much worth a read: Mark Amory, ed., The Letters of Evelyn Waugh. (You can get a taste of one of Waugh's letters, recounting one of his outrageous experiences in the war, here, read by Geoffrey Palmer.)

I found it an interesting exercise to read his letters alongside his Diaries, trying to pair them up whenever possible to see what he was saying publicly in a letter on a given day and then more or less privately in his diaries.

Fathers and Sons is in a category of its own as far as biographical studies are concerned. It was written and published in 2004 by Waugh's grandson Alexander (who, at last report, is editing all of his grandfather's works to appear in an opera omnia from Oxford University Press at some point). It is a wonderful book as much for its winsome style as its revealing discussion of Evelyn Waugh, his son the journalist Auberon (whose Will This Do? the First Fifty Years of Auberon Waugh: An Autobiography was, I thought, a bit of a dud), and the "family business" of writing.

Finally in this category, and a suitable bridge as we turn next to his novels, one simply must read Paula Byrne's 2011 book, Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead, a hugely entertaining and deeply fascinating study of some of the real life family and friends who were, mutatis mutandis, behind some of the characters who occupy Waugh's most famous novel, Brideshead Revisited. (A similar, though not nearly as interesting, study was attempted by Humphrey Carpenter in Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh and His Friends.)

Novels:

As just noted, Brideshead Revisited was a huge best-seller upon publication in 1945 and made Waugh a very wealthy man; and it has remained his best known work ever since, thanks not least to the lavish and lovely 1981 television adaptation featuring such illuminaries as Sir John Gielgud, Sir Laurence Olivier, and a young Jeremy Irons. For viewers of 2016: this 1981 series was the Downton Abbey of its time. If you have not seen it, then you simply must. (Pray do not pay the slightest heed to the wretched and beastly movie that came out in 2008 purporting to be based on Waugh's novel. It was, to use a Waughism, "too, too sick-making." As Charles Ryder's father from Brideshead would have said of the movie, "Such a lot of nonsense.") Jeremy Irons is also the reader for the audio book version of the novel, which is fantastic for long car rides.

Brideshead, for more than 70 years, has remained the best-known of his works, as I noted, but Waugh came to find the book distasteful in some ways, not least, as he later admitted, because it was deliberately written in a lush, lavish, luxuriant style, with great attention to food, wine, and wealth while he was a serving solder during the Second World War, with all the sensual deprivations of wartime Britain under severe rationing.

During the 1950s he traveled to Hollywood to negotiate a film deal about the novel, but it fell through in part because it featured an adulterous and divorced couple which American censorship rules of the time would not permit to be shown on screen. Waugh was just as glad it did not come to pass as he found the would-be producers totally obtuse and tone-deaf to the novel, which he regarded not as a paean to wealth or an encomium for the loss of the British aristocracy but as a lesson in the operation of divine grace.

It is on this point--how grace operates, and what it does, but especially does not do--that I think Brideshead is such a bracing corrective to too much of modern Christianity, perhaps especially in its moralistic-therapeutic North American versions of success and prosperity. The character clearly made out to be the worst in the novel--the morally degenerate, sexually disordered alcoholic Sebastian--emerges at the end to be the holiest of his family, spending his remaining days in the lowliest toil at a North African monastery, where he is treated as something of a joke: half-in, half-out the monastery, bottles of brandy hidden about the garden for a bender a few days of the month before pulling himself together again and appearing once more at chapel, repentant and sober (more or less).

His pseudo-saintly mother--whom the Joel Osteens of this world would gladly salute for her riches and apparent success--was a misguided and largely destructive force whose treacly piety does not adequately mask her libido dominandi, especially that directed at her adulterous husband ("that Reinhardt nun, my dear, has destroyed him but utterly," as Anthony Blanche memorably and accurately puts it, noting that she "has convinced the world that Lord Marchmain is a monster"). She screws up her own life and that of all her children, though they each in turn add to their woes. (Her friends, too, fare no better: "She sucks their blood" as Blanche says.) But grace does not swoop down to rescue any of them (just as their enormous wealth does not protect them either) from all the ill effects of their sin. Sebastian is "saved" in the end, but only as through fire; grace perfects and transforms nature, but the scars remain, as even the body of the resurrected Christ makes clear.

Brideshead appeared relatively late in Waugh's career, even if he was only 42 at its advent. He had, long before the war, made his mark for such novels as Decline and Fall (1928), Vile Bodies (1930), Black Mischief (1932), and A Handful of Dust (1934). These satirical-comical novels treated, inter alia, the vapidities of the inter-war generation of "bright young things" (of whom Waugh himself was sometimes accounted a part) and the vacuous promises of "progress," a word and concept that never failed to move Waugh to mockery ("Progress is a word that must be dismissed from our conversation before anything of real interest can be said"). By these novels he also became widely acclaimed as the great chronicler of the bright young things

Black Mischief in particular got him in some trouble by the editor of the Tablet, an obtuse sycophant who did not appreciate Waugh's satire about such things as African cannibalism. (One can only imagine the shrieking outrage of the banshees on Twitter were a publisher courageous enough to bring out such a book today.) This novel also made clear Waugh's lifelong disdain for "this revolting age" with all its preening technological advances and social "progress" that do nothing but cover over its moral, artistic, and spiritual bankruptcy. The longer the 20th century went on, the darker Waugh's vision of it became, so that by the time (1949) he would write the preface to Thomas Merton's Elected Silence he would say "the modern world is rapidly being made uninhabitable by the scientists and the politicians."

My favourite novel from this period is Scoop, published in 1938. It is loosely based on Waugh's real-life adventures as a journalist paid by London papers to report from Abyssinia on the imperial coronation of 1930 mentioned above. Anyone who thinks the laziness and mendacity of journalists which Waugh mocks in this novel are a thing of the past has simply not been paying attention to today's shenanigans. As Conrad Black, himself an erstwhile London newspaperman, noted several years ago,

a substantial number of journalists are ignorant, lazy, opinionated, and intellectually dishonest. The profession is heavily cluttered with aged hacks toiling through a miasma of mounting decrepitude and often alcoholism, and even more so with arrogant and abrasive youngsters who substitute 'commitment' for insight.

Historical-Biographical-Fictional Works:

The 30s were Waugh's most productive period because in addition to all the foregoing, he also produced a prize-winning historical-fictional account of the martyrdom of the Jesuit priest Edmund Campion. Written in a restrained, rather formal style, this book, published in 1935, was one of several semi-fictionalized treatments of important Catholic figures. Waugh felt that this book was, in part, a re-payment of personal debts owed to the Jesuits, not least the Jesuit priest, Martin D'Arcy, who instructed him and received him into the Church in 1930. It was also something of an aide-mémoire, reminding audiences of the 1930s that the martyrdom of Catholic clergy in 16th- century England had contemporary and ongoing parallels in those martyrdoms then occurring in the violence of revolutionary Mexico, which Waugh treated in Robbery Under Law (about which more below).

Two other such studies would follow, but not until the 1950s:

Helena (1950) was regarded by Waugh (according to Patey) as his true magnum opus. It is a short book, but full of buried jokes and puns, deliberately anachronistic speech, and political pot-shots at the socialism of the Atlee government. Waugh--who was often falsely accused of sucking up to the aristocracy and upper classes--deliberately chose to write about the life of the dowager empress of the Roman Empire in part because as the richest and most powerful woman of her time she showed that wealth and power were not, per se, obstacles to sanctity. (And Helena is indeed a canonized saint in the Catholic Church, and feted by Byzantine Christians as "co-equal to the apostles" along with her emperor son Constantine.) Moreover, he liked her, as he explains in his letters, because of her understanding of vocation: it did not necessarily require being thrown to the lions, or living in a desert eating locusts.

I love Helena not only for the humour but especially for her description of the feast of Epiphany/Theophany, and for what she says about the gifts brought by the wisemen, gifts that were not needed but "were accepted and put carefully by, for they were brought with love. In that new order of charity that had just come to life, there was room for you, too.....For His sake who did not reject your curious gifts, pray always for the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the Throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom."

Finally from this period, a formal, factual, and authorized biography, published in 1959, was devoted to Waugh's friend, the Roman Catholic convert, priest, and scholar: The Life of the Right Reverend Ronald Knox: Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford and Protonotary Apostolic to His Holiness Pope Pius XII. It is a slender study in a highly formalized style that does not pretend to be exhaustive. It, too, was repayment of a debt of sorts, and also, I think, something of a plaidoyer for Knox, whom Waugh and others felt had been badly treated by the English bishops, perhaps out of envy at Knox's superior education and background.

Semi-Autobiographical Works:

Waugh, though nearly 40 when war broke out, was desperate to obtain a position serving because he thought that wartime adventures would give him fresh material for later novels, and in this he was right. George Weigel has retailed some (possibly apocryphal) tales about Waugh's military service, including needling people by asking whether “in the Romanian army no one beneath the rank of Major is permitted to use lipstick.” And Patey's biography gives us tales of Waugh's researches in Tito's Yugoslavia. Waugh came to loathe Tito for his vicious persecution of Christians, and began a long campaign of mocking Tito as really a lesbian, whom he called "Auntie." ("Her face is pretty, but her legs are very thick.")

His resultant war trilogy is based in part on his own experiences, and has been acclaimed as one of the most realistic portrayals of what actual wartime service was like.

That trilogy was also turned into a movie which is not bad at all: Sword of Honour stars Daniel Craig and Nick Bartlett, inter alia.

Desperate to get out of England after the war, especially during the winter, and desperate therefore for a trip to warmer climes that someone else would pay for, Waugh undertook a number of trips, including most infamously a sea voyage in January 1954 for Rangoon. Waugh at this point in his life was plagued with boredom, melancholy, and insomnia. To deal with all three, but especially the latter, he was accustomed to regular imbibing of pharmacologically primitive sleeping potions liberally taken with large splashes of crème de menthe (on top of copious drinking during the day--gin, claret, champagne, wine). Over time, these sleeping draughts were slowly intoxicating him in what would be medically diagnosed as bromide psychosis, causing the fantastic delusions and hallucinations he had aboard the ship. Instead of hiding this embarrassing escapade, he used it as the basis for what he openly acknowledged was his most heavily autobiographical novel, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, which is also available in audio form. After he returned and went through a period of detox, he gleefully reported to friends "I've been mad!" and "I was clean off my onion!" He then adapted these experiences for use in Pinfold.

Finally, Waugh attempted an actual autobiography, A Little Learning. It is a laconic work and clearly Waugh's heart was not really in it. He never finished it: this is the first of what were expected to be at least two volumes. Published in 1964 less than two years before his death, this book only goes up to Waugh's suicide attempt in 1925 which, like the book itself, was rather desultory and manifestly incomplete. Waugh died before bringing out a second volume, but even before undertaking the writing of this one, his diaries and letters are full of his worries that his writing days were over, that he saw nothing but boredom and tedium in the years ahead, and that he had run out of anything fresh to say.

In addition, his spirits were not helped by the Second Vatican Council, whose reforms, he confessed, had knocked the stuffing out of him, making attendance at church now "pure duty parade." He regarded the liturgical reforms above all with nothing short of horror and was glad that his life would not last long enough to have to endure further changes. He confessed to family and friends that the council had sucked the last bits of joy from his life, and everyone agreed that his death, on Easter Sunday itself in 1966 shortly after hearing Mass in the traditional form he loved so well, was something he greatly welcomed. (Had he further exposure to the clunky, graceless, ideologically driven English translations of the Mass, one could well imagine Waugh saying of the translators what he himself said of the socialist writer Stephen Spender: ''to see him fumbling with our rich and delicate language is to experience all the horror of seeing a Sèvres vase in the hands of a chimpanzee.'')

Waugh's disgust with the changes, and especially with the mendacity and treachery of the hierarchy in the 1960s, comes through in a short but powerful little book, A Bitter Trial: Evelyn Waugh and John Carmel Cardinal Heenan on Liturgical Changes. Waugh was not, however, solely against John XXIII or Paul VI. He regarded Pope Pius XII as a villain for his reforms (also brought about by Bugnini) to Holy Week services, which Waugh felt had been completely wrecked in the name of restoring so-called earlier usages.

Political and Occasional Works:

Waugh made no secret of his disdain for modern politics. He hated being at parties where people wanted to talk politics, and found the whole area tedious. In the run-up to the 1959 election, the Spectator asked him to write a short piece, which he did: "Aspirations of a Mugwump," published in The Essays, Articles and Reviews of Evelyn Waugh. This collection, edited by Donat Gallagher, is absolutely invaluable for collecting a lot of Waugh's short and early pieces--essays, book reviews, and other doggrel he wrote to earn money before he made it into the big leagues.

In his short 1959 essay, Waugh noted that "I have never voted in a parliamentary election. I shall not vote this year." He regarded the whole process as a "very hazardous process" for the Sovereign to choose ministers. Calling popular election a source of "many great evils," he ended thus: "I do not aspire to advise my sovereign in her choice of servants."

For all his voluble disdain of politics, however, he did give it some sustained attention in what is perhaps his least known non-fiction work, viz., Robbery Under Law. This was a study he undertook after a paid trip to Mexico to see what life was like after the revolution there. He memorably described himself as a "conservative" after that trip, saying, inter alia:

Civilization has no force of its own beyond what is given it from within. It is under constant assault and it takes most of the energies of civilized man to keep going at all. There are criminal ideas and a criminal class in every nation and the first action of every revolution, figuratively and literally, is to open the prisons. Barbarism is never finally defeated; given propitious circumstances, men and women who seem quite orderly, will commit every conceivable atrocity. The danger does not come merely from habitual hooligans; we are all potential recruits for anarchy. Unremitting effort is needed to keep men living together at peace; there is only a margin of energy left over for experiment however beneficent. Once the prisons of the mind have been opened, the orgy is on.American civilization was one with which Waugh had an ambivalent relationship. There was much in 1950s America he admired, and American audiences made him very rich, not least when Brideshead was a Book of the Month pick, and sold well over 100,000 copies in the US alone. But American treatments of death provoked what is perhaps Waugh's most masterful work of social satire, the 1948 novella The Loved One. It is a brutal fictionalized take-down of the treacly euphemisms emanating from and the vulgar death-denying, money-making machinations of the gruesome funeral industry, a parallel to the non-fiction and equally scathing work of Waugh's compatriot Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death.

There is more that could be said about Waugh, and further works that could be discussed, but this covers his main works and is sufficient, I trust, to illustrate my main point: tolle, lege.

|

| Our Hero in His Library |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Anonymous comments are never approved. Use your real name and say something intelligent.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.