The Orthodox writer Jim Forest reminded me on Facebook that today is the 70th anniversary of the death of Mother Maria Skobtsova. (An excellent collection of resources about her may be found on the In Communion website.) Killed in the Ravensbrück concentration camp as the war in Europe was almost over, she was canonized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2004.

I was thinking about her extraordinary and staggering life again last week as I was finishing up what I hope to be the final edits to one of my forthcoming books (more on that later), a collection of papers from the Huffington Ecumenical Institute's 2012 symposium on Orthodoxy and the local Church in North America. One of the contributors, Fr. Justin Mathews, a priest of the OCA and founder of FOCUS, was discussing how inspirational Mother Maria's life was for those who, like him, have been working with the poor on the streets of North America--just as she worked with the poor, with Russian refugees, and with Jews hiding from the Nazis, on the streets of Paris. A political radical who may have wanted to see Trotsky assassinated, she was divorced twice, and in these and many other ways was nobody's idea of a nun, still less a "saint." And yet, as we contemplate this week the sacrificial self-offering of One on behalf of many, we see clearly that she too offered her life as a holy oblation outside the city in witness to Christ and in defense of His people--and long before that had served those people with a radical hospitality that many of us still need to learn.

Forest was the editor and compiler of a book of her writings: Mother Maria Skobtsova: Essential Writings (Orbis, 2002).

He also put together a charming book about her life suitable for children: Silent as a Stone: Mother Maria of Paris and the Trash Can Rescue.

Sergei Hacke's 1981 biography is still available: Pearl of Great Price: The Life of Mother Maria Skobtsova, 1891-1945.

And finally my friend Michael Plekon has a good chapter on her life in his collection, Living Icons: Persons of Faith in the Eastern Church.

"Let books be your dining table, / And you shall be full of delights. / Let them be your

mattress,/And you shall sleep restful nights" (St. Ephraim the Syrian).

mattress,/And you shall sleep restful nights" (St. Ephraim the Syrian).

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

Mother, Martyr, Saint: On the Death of Maria Skobtsova

Labels:

Jim Forest,

Mother Maria Skobtsova

Monday, March 30, 2015

Canon Law and Episcopal Authority

I recently attended a colloquium with Judge Michael Talbot, chief justice of the Michigan Court of Appeals and also the chairman of the Review Board for the Archdiocese of Detroit. He gave utterly fascinating insights into how, as a civil lawyer in private practice and then a judge in Michigan for decades, he had to learn a radically different legal culture when he entered the world of canon law and began dealing with ecclesiastical organs and tribunals attempting to root out clerical sexual abuse. The differences he discussed were very considerable--sometimes a cause for wonder, sometimes a cause for despair. But fascinating nonetheless.

In our discussion, I raised with him some of the early canons about clerical abuses, and their complete intolerance for any of this activity (even consensual activity). He noted that unlike Anglo-American law, canon law does not have a healthy doctrine of stare decesis and thus legal precedent does not carry the same weight. As a result, earlier canons can safely be ignored. As I was reflecting on this, it occurred to me that this may well be because canon law is concerned above all with the salvation of souls, and thus there are substantial theological reasons behind this different legal culture.

But this is not to say that precedent is irrelevant, or past canons carry no weight. No Eastern Christian would say that. But what weight should they have? Which canons are still important today, and which can safely be left behind? A new book, set for release this summer, will help us grapple anew with old canons still of enormous relevance to Orthodox-Catholic relations and the vexed question of the papacy. Did the papacy ever function as an "appellate court" as it were in the early Church, hearing cases from patriarchates and dioceses unable to resolve them independently? That question has long needed more consideration, and in Christopher Stephens, Canon Law and Episcopal Authority: The Canons of Antioch and Serdica (Oxford, 2015) it should at long last get it.

About this book we are told:

5. Law, Authority, and Power

6. Constantine, Control and Canon Law

In our discussion, I raised with him some of the early canons about clerical abuses, and their complete intolerance for any of this activity (even consensual activity). He noted that unlike Anglo-American law, canon law does not have a healthy doctrine of stare decesis and thus legal precedent does not carry the same weight. As a result, earlier canons can safely be ignored. As I was reflecting on this, it occurred to me that this may well be because canon law is concerned above all with the salvation of souls, and thus there are substantial theological reasons behind this different legal culture.

But this is not to say that precedent is irrelevant, or past canons carry no weight. No Eastern Christian would say that. But what weight should they have? Which canons are still important today, and which can safely be left behind? A new book, set for release this summer, will help us grapple anew with old canons still of enormous relevance to Orthodox-Catholic relations and the vexed question of the papacy. Did the papacy ever function as an "appellate court" as it were in the early Church, hearing cases from patriarchates and dioceses unable to resolve them independently? That question has long needed more consideration, and in Christopher Stephens, Canon Law and Episcopal Authority: The Canons of Antioch and Serdica (Oxford, 2015) it should at long last get it.

About this book we are told:

Christopher Stephens focuses on canon law as the starting point for a new interpretation of divisions between East and West in the Church after the death of Constantine the Great. He challenges the common assumption that bishops split between "Nicenes" and "non-Nicenes," "Arians" or "Eusebians." Instead, he argues that questions of doctrine took second place to disputes about the status of individual bishops and broader issues of the role of ecclesiastical councils, the nature of episcopal authority, and in particular the supremacy of the bishop of Rome.Part Three: Canon Law and Episcopal Authority

Canon law allows the author to offer a fresh understanding of the purposes of councils in the East after 337, particularly the famed Dedication Council of 341 and the western meeting of the council of Serdica and the canon law written there, which elevated the bishop of Rome to an authority above all other bishops. Investigating the laws they wrote, the author describes the power struggles taking place in the years following 337 as bishops sought to elevate their status and grasp the opportunity for the absolute form of leadership Constantine had embodied.

Combining a close study of the laws and events of this period with broader reflections on the nature of power and authority in the Church and the increasingly important role of canon law, the book offers a fresh narrative of one of the most significant periods in the development of the Church as an institution and of the bishop as a leader.

Introduction

Part One: The Canons of Antioch

1. The Canons of Antioch and the Dedication Council

2. The Canons of Antioch in Context

Part Two: Antioch and Serdica

3. The Dedication Council

4. Serdica, Rome, and the Response to Antioch

5. Law, Authority, and Power

6. Constantine, Control and Canon Law

Labels:

Antioch,

Canon Law,

Ecclesiology,

episcopal authority,

Serdica

Friday, March 27, 2015

Trinitarian Theology and Disability: an Interview with the Tataryns

At the end of February, I was at Baylor University at the Wilken Colloquium, devoted this year to the theme of eschatology. One of the speakers was the Reformed theologian J. Todd Billings, who gave a memorably moving presentation based on his new book, which is itself based on his life as a young man given a diagnosis of incurable cancer: Rejoicing in Lament: Wrestling with Incurable Cancer and Life in Christ (Brazos, 2015). In the discussion afterwards he noted that we still have not seen enough theological reflection on what it is like, and what it means, to live with a chronic condition, a major handicap, or a terminal diagnosis. I thought at the time of a recently published book, Discovering Trinity in Disability: A Theology for Embracing Difference (Orbis 2013), 144pp.

The book is co-authored by a Ukrainian Catholic priest-academic and his wife, also an academic, about their life with their three daughters. As such, they are immersed in the world of Eastern Christianity. Fr. Myroslaw, in fact, is author of other works, including How to Pray with Icons as well as an early and still-important study on the role and reception of Augustine of Hippo: Augustine and Russian Orthodoxy.

I asked Fr. Myroslaw and Pres. Maria for an interview, and here are their thoughts:

AD: Tell us about your backgrounds

Myroslaw is a Ukrainian Catholic priest and Doctor of Theology. He has served as pastor in Ontario and Saskatchewan (currently in Kitchener) and a professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Toronto, and, presently, Waterloo, where he has also been Dean and Acting President at St Jerome’s University.

He is married to Maria whose doctorate is in English, with a specialization in Literary Disability Studies. She has been the primary caregiver for their 3 daughters and an advocate for disability rights.

AD: What led to the writing of this book?

Although we had been entirely conscious of how our daily lives are permeated with the intersecting issues of disability, theology, culture, and justice, the real impetus for this collaborative project simply came from the publisher’s request. Without the outside proposal, daily life forever obstructed our desire to write together. Everything else seemed to take priority.

AD: Through much of this book, but especially in Maria's "Why We Wrote This Book," you've both put yourselves out there more than most "normal" academics would in writing, where we often treat issues in a dry, detached, clinical manner. The more personal side of our life has, in some ways, been bred out of us through graduate programs. Did you find it a struggle or a liberation (or both?) to be more directly personal about your own struggles and those of your family?

I, Maria, found it intensely difficult to include our personal life in this writing. In any academic work, I believe it is critical to disclose our ideological standpoint, or as much as possible to reflect on how our thinking is fueled by our personal experiences. My life with disability had compelled my work in disability studies, but for me, using family examples was uncomfortable and even invasive. However, we were instructed to write for an audience that was not strictly academic; our editors felt the personal was important. Unlike for me, Myroslaw, did find writing the personal experience somehow liberating. He included the excerpts from our life at the end of chapters and I, reluctantly, conceded.

AD: Also in that section, Maria, you note your entirely understandable frustration, which I share completely, with the usual shower of treacly pious cliches that rained down on you as a child when your father died. Has that changed at all in the intervening years--do you think Christians today are any better at resisting the usual tropes ("it's for the best" or "he's in a better place" or "don't be said--he's with Jesus in heaven!") that surround death in our culture today?

What an interesting question! Unfortunately, I think not. Understandably, because our mainstream culture still promulgates myths of control both in and of life (especially now promoting choice over when to die) death, grief, pain is strangely medicalized, sterilized, so that it is, as an event, removed from the normal. When faced with death, people, Christians or not, are simply not enculturated with responses beyond the reigning clichés. We want and need to feel helpful, comforting, and, in the moment, the tired tropes invariably revive.

AD: That section ends almost cryptically by declaring "We searched our faith tradition for signs of disability and, indeed, we found the Divine Trinity" (p.7). Tell us more what you meant by that.

Simply, we set out to find and

analyze images of disability in the Bible and in theology. Foundational texts

of disability studies in the humanities regularly indicted the Christian

tradition for much of the oppression suffered by people with disabilities and

indeed, voices of disabled people persistently spoke of exclusion and pain

suffered in their churches. In popular understanding, the Judeo-Christian

tradition viewed disability either as a mark of sin, divine disfavour, or

testing: a Job-like trial to see if you’ll go to the devil! God has singled you

out...

Simply, we set out to find and

analyze images of disability in the Bible and in theology. Foundational texts

of disability studies in the humanities regularly indicted the Christian

tradition for much of the oppression suffered by people with disabilities and

indeed, voices of disabled people persistently spoke of exclusion and pain

suffered in their churches. In popular understanding, the Judeo-Christian

tradition viewed disability either as a mark of sin, divine disfavour, or

testing: a Job-like trial to see if you’ll go to the devil! God has singled you

out...

So we wanted to examine some of the classic biblical passages used to devalue people with physical and/or mental impairments to determine if popular conceptions concurred with text and exegesis. This is why “we searched our faith tradition for signs of disability.” Of course, this search could constitute a life’s work with volumes of material. We delved into an example or two from a theological period and then jumped over centuries into another one. Nevertheless, we had not expected what we found. I, for one, grew up knowing that the doctrine of the Trinity was a mystery impossible to fathom. The shamrock provided a visual, but honestly—that symbol linked too quickly to leprechauns and beer drinking!

Investigating images of disability in our theological tradition illuminated the understanding of God as Trinity. Through our Judaic history, our record of Christ’s life and the development of the church, tracing the response to human vulnerability and difference reveals the inevitability of a Trinitarian God. Tracing the Christian reflection of Christ’s response to difference, impairment, alienation, erases the mystery of Trinity; disability seen with Christ makes the Trinity make sense. God is community: interdependent, inclusive, inviting, and embracing. God cannot be one: independent, solitary, autonomous (traits we North Americans value). God is love and love must go beyond self. It was a revelation, to look for disability and to find Trinity.

AD: Your introduction notes the work of Jean Vanier in bringing to the world's attention the plight of disabled people and how they are often appallingly treated. How influential was Vanier in your writing this book?

Vanier’s work did not directly inform ours. However, Jean Vanier, as a Christian, echoes Christ’s example of resisting mainstream norms to illuminate and value our shared and endlessly variable humanity. Vanier’s life reinforces the Christian tradition we highlight in our work.

AD: Your introduction notes that Christian communities may be good at rallying after an initial crisis or tragedy, but fade away quickly as people assume governments and social-service agencies will take their role. What can Christian communities do today to be more involved in helping people in need over the long haul?

If we believe that community necessitates relationship amongst members, then the answer to this question is alarmingly simple: we maintain a relationship with the disabled individual, even if they have ceased to run bake sales or attend services. Every person’s circumstance will be specific. A church community may not be able to provide specialized medical care, if it should be needed, but a community may always ensure that its members feel wanted and relevant, no matter the state they may be in. A community can ensure that members are not isolated, forgotten, lonely. Medicalized treatments and services play an important role in our lives, but they do not supplant the vital need for genuine caring relationship that a church community can and must provide if we aim to follow Christ. When a community cares for its members, no one person can feel burdened by giving or receiving care. Shared actions of love and care energize and motivate the Trinitarian dynamic represented in the icon that we describe in our book.

AD: You argue that "there is no one (definitive) definition of disability....Disability affects every person in society" (p.18) and yet I don't think we really realize this because, as you note, they are hidden away, or labeled as "special" or otherwise treated from a distance as "different" or "other." How can churches help avoid this ostracization, this distanciation, this "othering," and instead come to see everyone as fully part of God's commonwealth?

How can churches help avoid this “othering”? How can churches mirror Christ’s love, generosity, and courage to oppose mainstream norms? This is the truly daunting challenge. To see the fullness of Christ in the incommensureable breadth of humanity entails a profound transformation of perspective that demands conscious determination and work. To live as Trinity, we must necessarily unlearn enculturated prejudice. To unlearn means that we must recognise the prejudice in us and our role in the oppression of those who are seen as different. This acknowledgement is much easier said than done. Our view of disabled lives as less valuable than non-disabled lives seems self evident, far from a constructed societal policy that derived from a historical period of expansionist power politics. Church communities, it seems to me, thrive on opportunities for growth and conversion to deeper spirituality. To unlearn disability as deviancy and to dispel our fear of difference can be propelled by church leadership, who can create the attitude and language of welcome and familiarity. It is contagious! It is possible and it is beautiful.

AD: You make a strong point (pp.94-95) about how labeling people as "special" is in some ways the equivalent of the old label of "leper." Tell us what you meant by that.

There is power and privilege in

belonging to a dominant “norm.” Cultural studies has demonstrated the unspoken

privilege of whiteness, for example. Why

was whiteness not “coloured” and subject to study? Similarly, when civil rights

movements developed into disability rights movements, the insulting language

surrounding people with disabilities began to change into what appeared as more

“positive” terms. But these were euphemisms for the same debilitating and

dehumanizing attitudes that existed before and generally remain today. Retarded

kids became special kids, but no one wants to be special any more than they

want to be retarded! “Special”, in the 1990’s, became the accepted term for

segregated, excluded, bullied, too costly. Even as parents, we’d be called

“special” in a way we could tell meant, thank God YOU are the special ones and

we are normal! One could feel good about distancing oneself from the disabled

person, by praising them as special (and turning away). One wouldn’t feel as

decent if one spat in the face of a disabled person and turned away. Hence, the special label

helped the labellers, not the labelled.

There is power and privilege in

belonging to a dominant “norm.” Cultural studies has demonstrated the unspoken

privilege of whiteness, for example. Why

was whiteness not “coloured” and subject to study? Similarly, when civil rights

movements developed into disability rights movements, the insulting language

surrounding people with disabilities began to change into what appeared as more

“positive” terms. But these were euphemisms for the same debilitating and

dehumanizing attitudes that existed before and generally remain today. Retarded

kids became special kids, but no one wants to be special any more than they

want to be retarded! “Special”, in the 1990’s, became the accepted term for

segregated, excluded, bullied, too costly. Even as parents, we’d be called

“special” in a way we could tell meant, thank God YOU are the special ones and

we are normal! One could feel good about distancing oneself from the disabled

person, by praising them as special (and turning away). One wouldn’t feel as

decent if one spat in the face of a disabled person and turned away. Hence, the special label

helped the labellers, not the labelled.

AD: You refer several times to how Jesus debunks ideas of "normalcy." Tell us more about that.

Jesus hung out with women, prostitutes, children, lepers, tax collectors, foreigners and pointed out the hypocrisy of spiritual leaders. Jesus was crucified for defying norms. Need I say more?

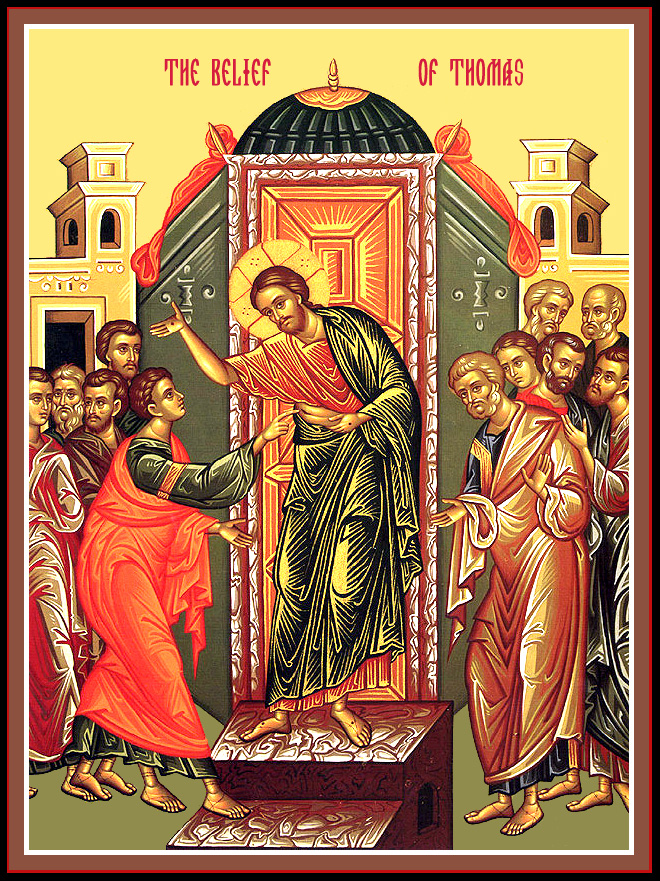

AD: You make various references throughout the book to Eastern Christians persons and practices--sacraments, Maximus the Confessor, Athanasius of Alexandria, etc. But in chapter 11 you talk in particular about the role of icons. Tell us how their portrayal of transfigured bodies is important to your arguments about embracing difference.

Icons do not try to present human bodies in anyone’s ideal form. There is no “normal” body. Humanity, all creation, is transfigured through Christ and as Christians we see material reality, each other as divine vessels. Only through creation can we come to know God. Physical variation in any form participates in the breadth and depth of divine revelation.

AD: One thing I've always been cheered by is that in the icons of the risen

Jesus, His "disability" as it were is transfigured but not hidden or

disappeared. In other words, His wounds are still visible, and I think

that's tremendously important to illustrating how God works--not by

covering up, hiding, pretending something didn't happen, or finding a

clumsy "work-around" but instead working through His disabling wounds.

AD: One thing I've always been cheered by is that in the icons of the risen

Jesus, His "disability" as it were is transfigured but not hidden or

disappeared. In other words, His wounds are still visible, and I think

that's tremendously important to illustrating how God works--not by

covering up, hiding, pretending something didn't happen, or finding a

clumsy "work-around" but instead working through His disabling wounds.

Yes. Our vulnerabilities/impairments bring us in touch with our physical reality, our humanness, and through our humanness we can come to know God.

AD: Sum up your hopes for this book, and who should read it.

We hope that believers and non-believers find value in the book. Believers who, by deepening their understanding of the Holy Trinity, become more radical in their willingness to see how we are all interdependent and so all, in our own unique manner, reflective of the Divine Life. Unbelievers who come to recognize that to be human is to be interdependent and that the idea of a human being as a solitary, unconnected entity is a myth that needs to be discarded. We hope that rather than seeing others as different, dangerous, or frightening we come to see each other as another face of the Divine Trinity.

The book is co-authored by a Ukrainian Catholic priest-academic and his wife, also an academic, about their life with their three daughters. As such, they are immersed in the world of Eastern Christianity. Fr. Myroslaw, in fact, is author of other works, including How to Pray with Icons as well as an early and still-important study on the role and reception of Augustine of Hippo: Augustine and Russian Orthodoxy.

I asked Fr. Myroslaw and Pres. Maria for an interview, and here are their thoughts:

AD: Tell us about your backgrounds

Myroslaw is a Ukrainian Catholic priest and Doctor of Theology. He has served as pastor in Ontario and Saskatchewan (currently in Kitchener) and a professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Toronto, and, presently, Waterloo, where he has also been Dean and Acting President at St Jerome’s University.

He is married to Maria whose doctorate is in English, with a specialization in Literary Disability Studies. She has been the primary caregiver for their 3 daughters and an advocate for disability rights.

AD: What led to the writing of this book?

Although we had been entirely conscious of how our daily lives are permeated with the intersecting issues of disability, theology, culture, and justice, the real impetus for this collaborative project simply came from the publisher’s request. Without the outside proposal, daily life forever obstructed our desire to write together. Everything else seemed to take priority.

AD: Through much of this book, but especially in Maria's "Why We Wrote This Book," you've both put yourselves out there more than most "normal" academics would in writing, where we often treat issues in a dry, detached, clinical manner. The more personal side of our life has, in some ways, been bred out of us through graduate programs. Did you find it a struggle or a liberation (or both?) to be more directly personal about your own struggles and those of your family?

I, Maria, found it intensely difficult to include our personal life in this writing. In any academic work, I believe it is critical to disclose our ideological standpoint, or as much as possible to reflect on how our thinking is fueled by our personal experiences. My life with disability had compelled my work in disability studies, but for me, using family examples was uncomfortable and even invasive. However, we were instructed to write for an audience that was not strictly academic; our editors felt the personal was important. Unlike for me, Myroslaw, did find writing the personal experience somehow liberating. He included the excerpts from our life at the end of chapters and I, reluctantly, conceded.

AD: Also in that section, Maria, you note your entirely understandable frustration, which I share completely, with the usual shower of treacly pious cliches that rained down on you as a child when your father died. Has that changed at all in the intervening years--do you think Christians today are any better at resisting the usual tropes ("it's for the best" or "he's in a better place" or "don't be said--he's with Jesus in heaven!") that surround death in our culture today?

What an interesting question! Unfortunately, I think not. Understandably, because our mainstream culture still promulgates myths of control both in and of life (especially now promoting choice over when to die) death, grief, pain is strangely medicalized, sterilized, so that it is, as an event, removed from the normal. When faced with death, people, Christians or not, are simply not enculturated with responses beyond the reigning clichés. We want and need to feel helpful, comforting, and, in the moment, the tired tropes invariably revive.

AD: That section ends almost cryptically by declaring "We searched our faith tradition for signs of disability and, indeed, we found the Divine Trinity" (p.7). Tell us more what you meant by that.

Simply, we set out to find and

analyze images of disability in the Bible and in theology. Foundational texts

of disability studies in the humanities regularly indicted the Christian

tradition for much of the oppression suffered by people with disabilities and

indeed, voices of disabled people persistently spoke of exclusion and pain

suffered in their churches. In popular understanding, the Judeo-Christian

tradition viewed disability either as a mark of sin, divine disfavour, or

testing: a Job-like trial to see if you’ll go to the devil! God has singled you

out...

Simply, we set out to find and

analyze images of disability in the Bible and in theology. Foundational texts

of disability studies in the humanities regularly indicted the Christian

tradition for much of the oppression suffered by people with disabilities and

indeed, voices of disabled people persistently spoke of exclusion and pain

suffered in their churches. In popular understanding, the Judeo-Christian

tradition viewed disability either as a mark of sin, divine disfavour, or

testing: a Job-like trial to see if you’ll go to the devil! God has singled you

out...So we wanted to examine some of the classic biblical passages used to devalue people with physical and/or mental impairments to determine if popular conceptions concurred with text and exegesis. This is why “we searched our faith tradition for signs of disability.” Of course, this search could constitute a life’s work with volumes of material. We delved into an example or two from a theological period and then jumped over centuries into another one. Nevertheless, we had not expected what we found. I, for one, grew up knowing that the doctrine of the Trinity was a mystery impossible to fathom. The shamrock provided a visual, but honestly—that symbol linked too quickly to leprechauns and beer drinking!

Investigating images of disability in our theological tradition illuminated the understanding of God as Trinity. Through our Judaic history, our record of Christ’s life and the development of the church, tracing the response to human vulnerability and difference reveals the inevitability of a Trinitarian God. Tracing the Christian reflection of Christ’s response to difference, impairment, alienation, erases the mystery of Trinity; disability seen with Christ makes the Trinity make sense. God is community: interdependent, inclusive, inviting, and embracing. God cannot be one: independent, solitary, autonomous (traits we North Americans value). God is love and love must go beyond self. It was a revelation, to look for disability and to find Trinity.

AD: Your introduction notes the work of Jean Vanier in bringing to the world's attention the plight of disabled people and how they are often appallingly treated. How influential was Vanier in your writing this book?

Vanier’s work did not directly inform ours. However, Jean Vanier, as a Christian, echoes Christ’s example of resisting mainstream norms to illuminate and value our shared and endlessly variable humanity. Vanier’s life reinforces the Christian tradition we highlight in our work.

AD: Your introduction notes that Christian communities may be good at rallying after an initial crisis or tragedy, but fade away quickly as people assume governments and social-service agencies will take their role. What can Christian communities do today to be more involved in helping people in need over the long haul?

If we believe that community necessitates relationship amongst members, then the answer to this question is alarmingly simple: we maintain a relationship with the disabled individual, even if they have ceased to run bake sales or attend services. Every person’s circumstance will be specific. A church community may not be able to provide specialized medical care, if it should be needed, but a community may always ensure that its members feel wanted and relevant, no matter the state they may be in. A community can ensure that members are not isolated, forgotten, lonely. Medicalized treatments and services play an important role in our lives, but they do not supplant the vital need for genuine caring relationship that a church community can and must provide if we aim to follow Christ. When a community cares for its members, no one person can feel burdened by giving or receiving care. Shared actions of love and care energize and motivate the Trinitarian dynamic represented in the icon that we describe in our book.

AD: You argue that "there is no one (definitive) definition of disability....Disability affects every person in society" (p.18) and yet I don't think we really realize this because, as you note, they are hidden away, or labeled as "special" or otherwise treated from a distance as "different" or "other." How can churches help avoid this ostracization, this distanciation, this "othering," and instead come to see everyone as fully part of God's commonwealth?

How can churches help avoid this “othering”? How can churches mirror Christ’s love, generosity, and courage to oppose mainstream norms? This is the truly daunting challenge. To see the fullness of Christ in the incommensureable breadth of humanity entails a profound transformation of perspective that demands conscious determination and work. To live as Trinity, we must necessarily unlearn enculturated prejudice. To unlearn means that we must recognise the prejudice in us and our role in the oppression of those who are seen as different. This acknowledgement is much easier said than done. Our view of disabled lives as less valuable than non-disabled lives seems self evident, far from a constructed societal policy that derived from a historical period of expansionist power politics. Church communities, it seems to me, thrive on opportunities for growth and conversion to deeper spirituality. To unlearn disability as deviancy and to dispel our fear of difference can be propelled by church leadership, who can create the attitude and language of welcome and familiarity. It is contagious! It is possible and it is beautiful.

AD: You make a strong point (pp.94-95) about how labeling people as "special" is in some ways the equivalent of the old label of "leper." Tell us what you meant by that.

There is power and privilege in

belonging to a dominant “norm.” Cultural studies has demonstrated the unspoken

privilege of whiteness, for example. Why

was whiteness not “coloured” and subject to study? Similarly, when civil rights

movements developed into disability rights movements, the insulting language

surrounding people with disabilities began to change into what appeared as more

“positive” terms. But these were euphemisms for the same debilitating and

dehumanizing attitudes that existed before and generally remain today. Retarded

kids became special kids, but no one wants to be special any more than they

want to be retarded! “Special”, in the 1990’s, became the accepted term for

segregated, excluded, bullied, too costly. Even as parents, we’d be called

“special” in a way we could tell meant, thank God YOU are the special ones and

we are normal! One could feel good about distancing oneself from the disabled

person, by praising them as special (and turning away). One wouldn’t feel as

decent if one spat in the face of a disabled person and turned away. Hence, the special label

helped the labellers, not the labelled.

There is power and privilege in

belonging to a dominant “norm.” Cultural studies has demonstrated the unspoken

privilege of whiteness, for example. Why

was whiteness not “coloured” and subject to study? Similarly, when civil rights

movements developed into disability rights movements, the insulting language

surrounding people with disabilities began to change into what appeared as more

“positive” terms. But these were euphemisms for the same debilitating and

dehumanizing attitudes that existed before and generally remain today. Retarded

kids became special kids, but no one wants to be special any more than they

want to be retarded! “Special”, in the 1990’s, became the accepted term for

segregated, excluded, bullied, too costly. Even as parents, we’d be called

“special” in a way we could tell meant, thank God YOU are the special ones and

we are normal! One could feel good about distancing oneself from the disabled

person, by praising them as special (and turning away). One wouldn’t feel as

decent if one spat in the face of a disabled person and turned away. Hence, the special label

helped the labellers, not the labelled.AD: You refer several times to how Jesus debunks ideas of "normalcy." Tell us more about that.

Jesus hung out with women, prostitutes, children, lepers, tax collectors, foreigners and pointed out the hypocrisy of spiritual leaders. Jesus was crucified for defying norms. Need I say more?

AD: You make various references throughout the book to Eastern Christians persons and practices--sacraments, Maximus the Confessor, Athanasius of Alexandria, etc. But in chapter 11 you talk in particular about the role of icons. Tell us how their portrayal of transfigured bodies is important to your arguments about embracing difference.

Icons do not try to present human bodies in anyone’s ideal form. There is no “normal” body. Humanity, all creation, is transfigured through Christ and as Christians we see material reality, each other as divine vessels. Only through creation can we come to know God. Physical variation in any form participates in the breadth and depth of divine revelation.

Yes. Our vulnerabilities/impairments bring us in touch with our physical reality, our humanness, and through our humanness we can come to know God.

AD: Sum up your hopes for this book, and who should read it.

We hope that believers and non-believers find value in the book. Believers who, by deepening their understanding of the Holy Trinity, become more radical in their willingness to see how we are all interdependent and so all, in our own unique manner, reflective of the Divine Life. Unbelievers who come to recognize that to be human is to be interdependent and that the idea of a human being as a solitary, unconnected entity is a myth that needs to be discarded. We hope that rather than seeing others as different, dangerous, or frightening we come to see each other as another face of the Divine Trinity.

Thursday, March 26, 2015

Dionysius, Thomas, and Albert Walk into a Bar...

Bearing an official release of today, this new book seems to be a good companion to read alongside Marcus Plested's splendid Orthodox Readings of Aquinas (I interviewed him here): Bernhard Blankenhorn, Mystery of Union with God: Dionysian Mysticism in Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas (CUA Press, 2015), 544pp.

About this book we are told by the publisher:

About this book we are told by the publisher:

Dionysius the Areopagite exercised immense influence on medieval theology. This study considers various ways in which his doctrine of union with God in darkness marked the early Albert the Great and his student Thomas Aquinas. The Mystery of Union with God considers a broad range of themes in the early Albert's corpus and in Thomas that underlie their mystical theologies and may bear traces of Dionysian influence. These themes include the divine missions, anthropology, the virtues of faith and charity, primary and secondary causality, divine naming, and eschatology. The heart of this work offers detailed exegesis of key union passages in Albert's commentaries on Dionysius, Thomas's Commentary on the Divine Names, and the Summa Theologiae questions on Spirit's gifts of understanding and wisdom. The Mystery of Union with God offers the most extensive, systematic analysis to date of how Albert and Thomas interpreted and transformed the Dionysian Moses "who knows God by unknowing." It shows Albert's and Thomas's philosophical and theological motives to place limits on Dionysian apophatism and to reintegrate mediated knowledge into mystical knowing. The author surfaces many similarities in the two Dominicans' mystical doctrines and exegesis of Dionysius. This work prepares the way for a new consideration of Albert the Great as the father of Rhineland Mysticism. The original presentation of Aquinas's theology of the Spirit's seven gifts breaks new ground in theological scholarship. Finally, the entire book lays out a model for the study of mystical theology from a historical, philosophical and doctrinal perspective.

Monday, March 23, 2015

Ephraim's Hymns of Faith

One of the loveliest aspects of the Great Fast in which we are all immersed currently is that it affords us the daily opportunity of reciting the prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian, that great father of Syriac Christianity, which Sebastian Brock has called the "third lung" of Christianity. Much in the Syriac tradition remains unknown and inaccessible, but gradually over the years we have been seeing a steady increase in good scholarly studies and translations, including this forthcoming volume set for release in mid-April: Ephraim the Syrian, The Hymns on Faith, trans. Jeffrey Wicks (Catholic University of America Press, 2015), 440pp.

Published in the highly respected "Fathers of the Church" series (book 130) of CUA Press, this book, the publisher tells us, will introduce us to:

Published in the highly respected "Fathers of the Church" series (book 130) of CUA Press, this book, the publisher tells us, will introduce us to:

Ephrem the Syrian, who was born in Nisibis (Nusaybin, Turkey) around 306 CE, and died in Edessa (Sanliurfa, Turkey) in 373. He was a prolific author, composing over four hundred hymns, several metrical homilies, and at least two scriptural commentaries. His extensive literary output warrants mention alongside other well-known fourth-century authors, such as Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil of Caesarea. Yet Ephrem wrote in neither Greek nor Latin, but in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic. His voice opens to the reader a fourth-century Christian world perched on the margins between the Roman and Persian Empires.

Ephrem is known for a theology that relies heavily on symbol and for a keen awareness of Jewish exegetical traditions. Yet he is also our earliest source for the reception of Nicaea among Syriac-speaking Christians. It is in his eighty-seven Hymns on Faith - the longest extant piece of early Syriac literature - that he develops his arguments against subordinationist christologies most fully. These hymns, most likely delivered orally and compiled after the author's death, were composed in Nisibis and Edessa between the 350s ans 373. They reveal an author conversant with Christological debates further to the west, but responding in a uniquely Syriac idiom. As such, they form an essential source for reconstructing the development of pro-Nicene thought in the eastern Mediterranean.

Yet, the Hymns on Faith off er far more than a simple Syriacpro-Nicene catechetical literature. In these hymns Ephrem reflects upon the mystery of God and the limits of human knowledge. He demonstrates a sophisticated grasp of symbol and metaphor and their role in human understanding.

The Hymns on Faith are translated here for the first time in English on the basis of Edmund Beck's critical edition.

Friday, March 20, 2015

Syriac Christians Envisioning Islam

Michael Phillip Penn, whose other publication this year on Syrians encountering Islam was noted here, has another book coming out in June that I'm eagerly looking forward to reading: Envisioning Islam: Syriac Christians and the Early Muslim World (U Penn Press, 2015), 320pp.

About this book we are told:

About this book we are told:

The first Christians to encounter Islam were not Latin-speakers from the western Mediterranean or Greek-speakers from Constantinople but Mesopotamian Christians who spoke the Aramaic dialect of Syriac. Under Muslim rule from the seventh century onward, Syriac Christians wrote the most extensive descriptions extant of early Islam. Seldom translated and often omitted from modern historical reconstructions, this vast body of texts reveals a complicated and evolving range of religious and cultural exchanges that took place from the seventh to the ninth century.

The first book-length analysis of these earliest encounters, Envisioning Islam highlights the ways these neglected texts challenge the modern scholarly narrative of early Muslim conquests, rulers, and religious practice. Examining Syriac sources including letters, theological tracts, scientific treatises, and histories, Michael Philip Penn reveals a culture of substantial interreligious interaction in which the categorical boundaries between Christianity and Islam were more ambiguous than distinct. The diversity of ancient Syriac images of Islam, he demonstrates, revolutionizes our understanding of the early Islamic world and challenges widespread cultural assumptions about the history of exclusively hostile Christian-Muslim relations.

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

In Honour of Thomas Hopko

The news has been circulating for more than a week that the Orthodox presbyter and theologian Thomas Hopko is in his last days. I met him briefly once in 2008 at the Sheptytsky Institute's "Study Days" that summer. It was there, I think, that I first heard his "55 Maxims of the Christian Life." It was there that I came to admire him as a plain-spoken, pull-no-punches type of man who clearly had no patience for obfuscation and nonsense. He was faithful to Orthodoxy and in doing so was unwilling to trim his sails because of political pressure to "make nice" to others. Those traits were on display in his book Speaking The Truth In Love: Education, Mission, And Witness In Contemporary Orthodoxy.

I have not always agreed with Hopko, as I note in my Orthodoxy and the Roman Papacy: Ut Unum Sint and the Prospects of East-West Unity. There I noted that on at least one occasion his spare style and restrained rhetoric seem to have been abandoned in favor of an absurdly inflationary list of things he wanted changed in the Roman Catholic Church. In his talk "Roman Presidency and Christian Unity in our Time," Hopko went on at length about dozens of issues that nobody else on the Orthodox side was writing or worrying about--nobody, that is, who was as intellectually serious as Hopko otherwise is. Moreover, as I argued, Hopko attributed--with enormous irony!--a massive power to the pope that (a) the pope has never had and today does not have; and (b) that the Orthodox would be the first to object to his having in the first place! I wrote off the paper as rather a fluke, and of the more than twenty Orthodox thinkers I reviewed in my book, demonstrated just how sui generis Hopko's list was. We all have bad days and bad ideas sometimes make it into print. This list did not affect my view that Hopko remains a serious and sober thinker.

But Hopko has produced other important books. Friends at Christmas several years ago gave Christ in the Old Testament: Prophecy Illustrated to my sons, and it is a charming and beautifully illustrated book thanks to the artistic talents of Niko Chocheli.

Several years ago now when I was trying to write a book on the importance of a clearly defined theology of sexual differentiation--the real issue underlying the push for the ordination of women and the recognition of same-sex "marriage"--I found Hopko's edited collection Women and the Priesthood very prescient in his claim that

Hopko, in a more focused treatment, returned to some of these issues in his short book Christian Faith and Same Sex Attraction: Eastern Orthodox Reflections.

As he prepares to "shuffle off this mortal coil" and stand before the "awesome tribunal of Christ," we can pray that because of these books and the rest of his life's work, he will hear the "Well done, good and faithful servant! Enter into the joy of your Lord" that we all long to hear on that day.

I have not always agreed with Hopko, as I note in my Orthodoxy and the Roman Papacy: Ut Unum Sint and the Prospects of East-West Unity. There I noted that on at least one occasion his spare style and restrained rhetoric seem to have been abandoned in favor of an absurdly inflationary list of things he wanted changed in the Roman Catholic Church. In his talk "Roman Presidency and Christian Unity in our Time," Hopko went on at length about dozens of issues that nobody else on the Orthodox side was writing or worrying about--nobody, that is, who was as intellectually serious as Hopko otherwise is. Moreover, as I argued, Hopko attributed--with enormous irony!--a massive power to the pope that (a) the pope has never had and today does not have; and (b) that the Orthodox would be the first to object to his having in the first place! I wrote off the paper as rather a fluke, and of the more than twenty Orthodox thinkers I reviewed in my book, demonstrated just how sui generis Hopko's list was. We all have bad days and bad ideas sometimes make it into print. This list did not affect my view that Hopko remains a serious and sober thinker.

But Hopko has produced other important books. Friends at Christmas several years ago gave Christ in the Old Testament: Prophecy Illustrated to my sons, and it is a charming and beautifully illustrated book thanks to the artistic talents of Niko Chocheli.

Several years ago now when I was trying to write a book on the importance of a clearly defined theology of sexual differentiation--the real issue underlying the push for the ordination of women and the recognition of same-sex "marriage"--I found Hopko's edited collection Women and the Priesthood very prescient in his claim that

Hopko went on to quote an even stronger formulation from (of all people) Luce Irigaray, who wrote that “Sexual difference is one of the major philosophical issues, if not the issue, of our age. … Sexual difference is probably the issue of our time which could be our ‘salvation’ if we thought it through." Such "thinking through" still awaits us, and I hope to finish an article on it perhaps late this summer.The question of women and the priesthood is but one important instance of what I perceive to be the most critical issue of our time: the issue of the meaning and purpose of the fact that human nature exists in two consubstantial forms: male and female. This is a new issue for Christians; it has not been treated properly in the past. But it cannot be avoided today.

Hopko, in a more focused treatment, returned to some of these issues in his short book Christian Faith and Same Sex Attraction: Eastern Orthodox Reflections.

As he prepares to "shuffle off this mortal coil" and stand before the "awesome tribunal of Christ," we can pray that because of these books and the rest of his life's work, he will hear the "Well done, good and faithful servant! Enter into the joy of your Lord" that we all long to hear on that day.

Labels:

Sexual Differentiation,

Thomas Hopko

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

Render Unto the Sultan

As I have repeatedly noted on here, there is much we still need to learn, or in some cases re-learn, about the encounters, varied and various according to time and place, between Eastern Christians and Muslims. That is as true for two neighbors encountering one another across the Anatolian plateau as it is for leaders at the highest levels of Church and empire. We need, moreover, to deepen our understanding of Church-state relations in the East if only so that we can finally move beyond tired stereotypes of "caseropapism" and other slogans. A book set for release early next month should shed welcome light here: Tom Papademetriou, Render unto the Sultan: Power, Authority, and the Greek Orthodox Church in the Early Ottoman Centuries (Oxford UP, 2015), 288pp.

About this book we are told:

The received wisdom about the nature of the Greek Orthodox Church in the Ottoman Empire is that Sultan Mehmed II reestablished the Patriarchate of Constantinople as both a political and a religious authority to govern the post-Byzantine Greek community. However, relations between the Church hierarchy and Turkish masters extend further back in history, and closer scrutiny of these relations reveals that the Church hierarchy in Anatolia had long experience dealing with Turkish emirs by focusing on economic arrangements. Decried as scandalous, these arrangements became the modus vivendi for bishops in the Turkish emirates.

Primarily concerned with the economic arrangements between the Ottoman state and the institution of the Greek Orthodox Church from the mid-fifteenth to the sixteenth century, Render Unto the Sultan argues that the Ottoman state considered the Greek Orthodox ecclesiastical hierarchy primarily as tax farmers (mültezim) for cash income derived from the church's widespread holdings. The Ottoman state granted individuals the right to take their positions as hierarchs in return for yearly payments to the state. Relying on members of the Greek economic elite (archons) to purchase the ecclesiastical tax farm (iltizam), hierarchical positions became subject to the same forces of competition that other Ottoman administrative offices faced. This led to colorful episodes and multiple challenges to ecclesiastical authority throughout Ottoman lands.

Tom Papademetriou demonstrates that minority communities and institutions in the Ottoman Empire, up to now, have been considered either from within the community, or from outside, from the Ottoman perspective. This new approach allows us to consider internal Greek Orthodox communal concerns, but from within the larger Ottoman social and economic context.

Render Unto the Sultan challenges the long established concept of the 'Millet System', the historical model in which the religious leader served both a civil as well as a religious authority. From the Ottoman state's perspective, the hierarchy was there to serve the religious and economic function rather than the political one.

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Jean Vanier on Loving Human Beings

Normally I find Canadian nationalism utterly risible, and a long time ago I developed an allergy to the pathetically passive-aggressive boosterism that some Canadians use (what is the current and apt portmanteau? "humblebragging"?) to try to prove their worth in the face of superior cultures. But in at least one instance, I am glad indeed to share the same terre de nos aïeux with this year's Templeton Prize winner, Jean Vanier. Axios!

I think I first heard Vanier (who has a lovely and lyrical speaking voice) during his 1998 Massey Lecture, and thereafter began to read him. I have remained haunted by this man's life and work for he is an example to all of us, but especially those of us who endanger our faith and humanity by being academics. Descended from a famously distinguished and much-decorated vice-regal family of deep Christian faith, Vanier could have had a conventional academic career, for which he received a doctorate in Paris. But truly here is a man who has heeded and embodied that famous Evagrian dictum that Eastern Christians are forever quoting to each other: the "theologian" is a man of prayer, of service, and of love. All the degrees in the world matter not a whit if you have not love, especially for the most unlettered and unloved of people, including, in Vanier's case, those "handicapped" people otherwise condemned to be warehoused away.

Vanier, appalled at such treatment, founded the now widespread international movement L'Arche, with 147 communities in 35 countries. L'Arche puts Christian hospitality into action, creating houses where "handicapped" people can love and be loved. Early on he helped me understand one thing clearly: people involved with serving others can often be prone to a kind of paternalism in thinking of themselves as only the givers, but in fact they often receive back far more than we give, and far more important gifts too. Moreover, Vanier, together with Henri Nouwen, helped me to realize that all of us are "wounded healers" and we need to be open to receiving from others even as we need also to be able to give. Vanier's life of heroic virtue shows us the wisdom that Charles Ryder utters in Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited: "to know and love one other human being is the root of all wisdom."

I think I first heard Vanier (who has a lovely and lyrical speaking voice) during his 1998 Massey Lecture, and thereafter began to read him. I have remained haunted by this man's life and work for he is an example to all of us, but especially those of us who endanger our faith and humanity by being academics. Descended from a famously distinguished and much-decorated vice-regal family of deep Christian faith, Vanier could have had a conventional academic career, for which he received a doctorate in Paris. But truly here is a man who has heeded and embodied that famous Evagrian dictum that Eastern Christians are forever quoting to each other: the "theologian" is a man of prayer, of service, and of love. All the degrees in the world matter not a whit if you have not love, especially for the most unlettered and unloved of people, including, in Vanier's case, those "handicapped" people otherwise condemned to be warehoused away.

Vanier, appalled at such treatment, founded the now widespread international movement L'Arche, with 147 communities in 35 countries. L'Arche puts Christian hospitality into action, creating houses where "handicapped" people can love and be loved. Early on he helped me understand one thing clearly: people involved with serving others can often be prone to a kind of paternalism in thinking of themselves as only the givers, but in fact they often receive back far more than we give, and far more important gifts too. Moreover, Vanier, together with Henri Nouwen, helped me to realize that all of us are "wounded healers" and we need to be open to receiving from others even as we need also to be able to give. Vanier's life of heroic virtue shows us the wisdom that Charles Ryder utters in Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited: "to know and love one other human being is the root of all wisdom."

Labels:

Brideshead Revisited,

Evelyn Waugh,

Henri Nouwen,

Jean Vanier,

L'Arche

Monday, March 9, 2015

Michael Martin on Sophiology

If you know nothing else about twentieth-century Orthodox theology, you have at least likely heard that some shadow of suspicion lies over Sergius Bulgakov in particular and sophiology in general. A new book tackles many of these questions head-on, and bears an impressive roster of "blurbers" on the back: the Orthodox Andrew Louth and Antoine Arjakovsky; the Catholic Francesa Aran Murphy; and the Anglican ("Radical Orthodox") John Milbank, all endorsing Michael Martin's new book, The Submerged Reality: Sophiology and the Turn to a Poetic Metaphysics (Angelico Press, 2015), 246pp. I asked Michael for an interview about this fascinating new book, and his very interesting life, and here are his thoughts.

AD: Tell us a bit about your background

I don’t know if we’re far from the controversy or not. My guess is that we aren’t. I’ve had a few scholars already question my investigation of this “heresy” (their words). I really don’t care. I really did feel called to write this book, so I trust in God and pray that good may come of it.

AD: Tell us a bit about your background

MM: I grew up in working-class Detroit in a working-class family. I hold

a Ph.D. in English from Wayne State University, specializing in early modern

literature, especially religious literature. I have worked as a musician,

bookseller, garden designer, Waldorf teacher (hence my interest in Rudolf

Steiner), and for the last fourteen years as a scholar and professor. I am also

a poet. I am married, a Byzantine Catholic, and I have nine children. My wife,

Bonnie, and I run a small organic farm close to Ann Arbor.

AD: What led to the writing

of this book?

MM: I’ve been interested in sophiology since hearing about it

twenty-five years ago when I first encountered the writing of Solovyov. While

working on my dissertation (since published as Literature and the Encounter With God in Post-Reformation England) and writing chapters on Jane Lead and Henry and Thomas Vaughan, I realized what

an important figure Jacob Boehme was to 17th century English

religion and literature—especially his introduction of Sophia to religious

awareness—and thought “somebody should write a book on that.” That “somebody”

turned out to be me. Originally, I planned on sticking to seventeenth-century England—there is more work to be done on the topic with Thomas Traherne

and the Cambridge Platonists, for instance—but John Riess of Angelico Press, who

was then preparing my poetry collection, Meditations in Times of Wonder for publication, approached me about doing a book and I

decided to do a book on sophiology more broadly conceived and from the 17th

century to the present. It was a fun book to write.

AD: For nearly the last

century, anything with the word "sophiology" in the title has tended

to make Eastern (esp. Russian) Christians nervous thanks to the controversy

around Bulgakov—a fact several of your reviewers note by variously calling your book

"brave," "daring" and "controversial."

Did you feel you were beginning under a shadow as it were—like someone presumed

guilty until proven innocent? Or are we far enough away now from controversy

that sophiology today no longer rings alarms for people (those who, rightly,

you say indulge in the "inherently ugly" business of heresy hunting)?

I didn’t feel I had anything to lose, but I did expect to be greeted

with a hostile reception. My pastor, a wise and scholarly man, was the only

person to look at any of the book before it came out—I showed him the first

chapter and the chapter on the Russians. He thought much of them, but said, “Michael,

my son, you’re going to make some people mad.” Looking at the history of

sophiology, I’d say that goes with the territory. I don’t know if we’re far from the controversy or not. My guess is that we aren’t. I’ve had a few scholars already question my investigation of this “heresy” (their words). I really don’t care. I really did feel called to write this book, so I trust in God and pray that good may come of it.

AD: What is it, in brief,

about sophiology that it seems to have been such a magnet for misunderstanding

and controversy?

Two things, I think. One: some people don’t like to think of Sophia

as a divine person (the “fourth hypostasis” anxiety). Two: the issue of gender.

Now, despite what John Milbank has suggested, I am no feminist theologian. But

I really don’t understand why some theologians get so freaked out when someone

suggests that we take the feminine Wisdom figure of Proverbs and the other

Wisdom books as feminine and not as code for “Logos.” Last night I was reading Augustine: On the Trinity—the Father as lover, the Son as beloved, and the

Spirit as the love between them. That may be a nice way to put it, but Sophia

is missing from the picture and would give it a more accurate, gendered

typology with real applications in our current cultural situation—and I am NOT

saying we need to add Sophia to the Trinity, just that we need to think about

gender (and how God works) differently when it comes to theology. Now, don’t

get me wrong, I love Augustine—we even named one of our children after him—but

classical culture was all about the dudes. As I argue in my book’s conclusion,

despite/due to feminism, gender difference has been rendered almost

inconsequential and even changeable. How’s that for heresy? A sophiological

approach could restore some balance and common sense to some aspects of

theology, not to mention philosophy and culture.

AD: Give us your brief

sketch of how you understand sophiology and why it is so important.

I understand sophiology as a poetic intuition, primarily, as a way

of perceiving. In this, it has much in common with phenomenology, for both are

grounded in contemplation. For one, contemplation is one way in which

Sophia—the Wisdom of God—is disclosed, is seen as shining through the

phenomenal world (von Balthasar’s notion of “splendor” is a great help in this

regard). This can happen through the natural world, through the arts, through

liturgy, through another person.

Sophiology is important because it offers a way to bring reverence

to scientific modes of inquiry and return beauty to the lexicons of both art

and theology. Sophiology asks us to be attentive to the possibility of God’s presence

in the phenomenal world, in history, in the human person, and in the cosmos.

AD: Your first chapter draws

on a vast and very impressive array of people ancient and modern, Eastern and

Western, philosophical and theological. But what I truly did not expect to find

was a disquisition on genetically modified organisms! Tell us how you see the

links in Western theological developments, Eastern ressourcement, and GMOs.

Well…rationality is not always a good thing, for one. I trace the problem

from the nominalist/realist debates of the Middle Ages to natura pura with early modern Neo-Scholasticism to scientific

materialism to our current, postmodern nominalist cultural milieu.

Sophiology—at least since Boehme—has been pushing against this trend.

My interest in the GMO issue is connected to my understanding of

farming. But the GMO issue, as well as transhumanism and the postmodern

dismissal of gender as a reality, all lead back to nominalism. For a postmodern

nominalist, GMO corn, for instance, maybe not genetically be corn. The

postmodern nominalist attitude is, basically, “So what? ‘Corn’ is just a name.”

Same with the human person: “gender is culturally determined.” There is

something, and I don’t mean this metaphorically, inherently demonic about such

language. Sophiology pushes against this extreme violence and, like

phenomenology and ressourcement,

returns “to the things themselves” in order to reset our notions of the real

against what is clearly a disordered state of affairs.

AD: Your fourth chapter treats

the "noble failure of romanticism." What was noble about it, and why

was it a failure?

What was noble about it was that the Romantics at least tried to

come to what I would call a religious intuition in their rejection of the

Enlightenment. It failed because it wasn’t grounded in the historical Church

and tried to realize that essentially religious intuition on its own. I greatly

admire their attempt to find the good at the center of the world. But you can’t

find it without Jesus. This is why, for me, of all the Romantics, Novalis comes

closest. He sensed, even more than Goethe, the importance of the Church to this

seeking. Had he lived (he died—on the feast of the Annunciation,

incidentally—before he turned thirty), he may have made it a reality.

AD: In that chapter, Goethe

features prominently. What role do you see for him in sophiology?

For me, Goethe’s great contribution is in introducing the concept of

“reverence” into scientific inquiry. His phenomenology is itself a kind of

sophiology, attentive to presence, beauty, and “things as they are.” He was suspicious

of ideology, especially scientific ideology, and such an attitude is truly

helpful for beholding and comprehending that which is before one. And the end Faust, part 2—when the Mater Gloriosa

rescues Faust from damnation—is some of the most beautiful sophiology/Mariology

I’ve read.

AD: Your conclusion notes

that a "complete sophiology has yet to be realized" in part because

of attempts to turn it into theology or doctrine. If it is not those latter two

things, or part of them, what is it? How would you characterize it? What is its

"genre" if you will?

I think it could be part of them, but I wonder if academic theology

would be welcome to such an idea. I doubt it, frankly. Academia, in my

experience, is a pretty politically-charged work environment generally hostile

to new ideas.

What I am envisioning for a “complete sophiology” is probably far

too idealistic, but here goes: I think it would include a complete teardown of

our current secularist worldview—a worldview that, as you know, almost totally

permeates Catholic higher education. The kind of sophiology I envision is one

that integrates science, art, and religion. I think this idea is beautifully

manifested in Henry Vaughan’s poetry wherein God, the natural world, and poetry

are united in a fully integrated whole. So, maybe it is best to say that such

an idea probably couldn’t be realized in the academy. But it could happen in

the context of a community (or communities).

Sophiology’s genre, as I argue in the book, is poetic. But I am thinking of “poetic” here as a way of perceiving, not necessarily as a form of writing. For me, like liturgy, a farm or a scientific discovery can be every bit as poetic as a poem. I follow Heidegger in that way: “All reflective thinking is poetic, and all poetry in turn is a kind of thinking.”

Sophiology’s genre, as I argue in the book, is poetic. But I am thinking of “poetic” here as a way of perceiving, not necessarily as a form of writing. For me, like liturgy, a farm or a scientific discovery can be every bit as poetic as a poem. I follow Heidegger in that way: “All reflective thinking is poetic, and all poetry in turn is a kind of thinking.”

AD: Sum up your hopes for

this book, and who should read it.

I hope the book can help reset the conversation about sophiology,

for one. For another, I hope it can offer people a way to rethink our

relationship to the created world and culture, the Church and the cosmos. I

also hope it can encourage some people to interrogate the

Enlightenment/scientific materialist assumptions about knowledge of the world

that our culture has interiorized to such an alarming (if, for the most part,

unconscious) degree.

Though I am an academic, I didn’t write the book only for my peers.

I wrote it for people interested in religious ideas, in ideas about what is

most important in human life. In a way, I think I had my eldest son and people

of his age in mind when I wrote the book. He’s twenty-five and I know how

people at that time of life are trying to find meaning in the world and are

often turned off (or away) from the religious discourses or communities

available to them. Beauty has a way of speaking to them directly and drawing

them more effectively to the Church than hours and hours of (often) sterile

apologetics. Sophiology, if nothing else, is engaged with beauty.

AD: Having finished this

book, what projects are you at work on now?

First, I

have been trying to finish an article on the Catholic specters in the poetry of

Robert Herrick and Nicholas Ferrar’s community at Little Gidding. I am also

preparing a sophiology casebook which will consist of about 120 pages of

primary source material (Boehme, Jane Lead, Goethe, Solovyov, Bulgakov, and so

forth), 75 pages of poetry (Blok, Novalis, Hopkins, Merton, etc.), and 7 or 8

critical essays. This summer, I hope to work on some new poetry and then get to

a book on poetics. I also have a garden to plant, some goats to milk, and a few

beehives to shepherd.

Friday, March 6, 2015

The Church in the Square

Though the Coptic Church is of course the indigenous church of Egypt, there are other Christian traditions extant in the country, not least Roman Catholics and evangelicals. What was striking to me in visiting Coptic churches the first few times now twenty years ago was the evidence of clear borrowing of certain practices from North American evangelicals. One such evangelical church in Cairo is the object of a book set for release later this spring.

The American University of Cairo Press just sent me their latest catalogue, and included a book set for release in May of this year: Anna Jeanine Dowell, The Church in the Square: Negotiations of Religion and Revolution at an Evangelical Church in Cairo (Cairo Papers in Social Science) (AUC Press, 2015), 112pp.

About this book we are told:

The American University of Cairo Press just sent me their latest catalogue, and included a book set for release in May of this year: Anna Jeanine Dowell, The Church in the Square: Negotiations of Religion and Revolution at an Evangelical Church in Cairo (Cairo Papers in Social Science) (AUC Press, 2015), 112pp.

About this book we are told:

In the wake of the January 25, 2011 popular uprisings, youth and leaders from the Kasr el Dobara Evangelical Church, the largest Protestant congregation in the Middle East, situated just behind Tahrir Square embarked on new, unpredictable political projects. This ethnography seeks to elucidate the ways that youth and leaders utilized religious imagery and discourse and relational networks in order to carve out a place in the Egyptian public sphere regarding public religion, national belonging, and the ideal citizen. Evangelical Egyptians at KDEC navigated the implications of their colonial heritage and transnational character even as their leadership sought to ground the congregation in the Egyptian national imagery and emerging revolutionary political scene. The author argues that these negotiations were built upon powerful paradoxes concerning liberal politics, secularism, and private versus public religion, which often implicated Evangelicals in the same questions being raised in public discourse concerning Islamist politics and religious minorities.

Labels:

Coptic history,

Copts,

Egypt,

Egyptian Christians,

Evangelicals,

Tahrir Square

Thursday, March 5, 2015

Languages and Cultures of Eastern Christianity III: Greek

Nearly four years ago now, when word first emerged that Ashgate was going to start this series, I posted notice of it and have since drawn attention to some of the earlier volumes. It remains the sort of indispensable collection of volumes that any serious and self-respecting library devoted to Eastern Christianity must have. The latest volume, just published after Christmas, is edited by Scott F. Johnson, whose previous works, including my interview with him, may be found here. This latest volume is Languages and Cultures of Eastern Christianity: Greek (Ashgate/Variorum, 2014), 480pp.

About this book we are told:

Preface

Introduction: the social presence of Greek in Eastern Christianity, 200-1200 CE;

Sextus Julius Africanus and the Roman Near East in the third century, William Adler;

Ethnic identity in the Roman Near East, AD 325-450: language, religion, and culture, Fergus Millar; Bilingualism and diglossia in late antique Syria and Mesopotamia, David Taylor;

The private life of a man of letters: well-read practices in Byzantine Egypt according to the Dossier of Dioscorus of Aphrodito, Jean-Luc Fournet;

Dioscorus and the question of bilingualism in sixth-century Egypt, Arietta Papaconstantinou;

Palestinian hagiography and the reception of the Council of Chalcedon, Bernard Flusin;

The Christian schools of Palestine: a chapter in literary history, Glanville Downey;

Embellishing the steps: elements of presentation and style in The Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus, John Duffy;

The works of Anastasius of Sinai: a key source for the history of seventh-century East Mediterranean society and belief, John Haldon;

Greek literature in Palestine in the eighth century, Robert Pierpont Blake;

Greek culture in Palestine after the Arab conquest, Cyril Mango;

Some reflections on the continuity of Greek culture in the East in the seventh and eighth centuries, Guglielmo Cavallo;

From Palestine to Constantinople (eighth-ninth centuries): Stephen the Sabaite and John of Damascus, Marie-France Auzépy;

The Life of Theodore of Edessa: history, hagiography, and religious apologetics in Mar Saba monastery in early Abbasid times, Sidney Griffith;

Why did Arabic succeed where Greek failed? Language change in the Near East after Muhammad, David Wasserstein;

From Arabic to Greek, then to Georgian: a life of Saint John of Damascus, Bernard Flusin;

Greek - Syriac - Arabic: the relationship between liturgical and colloquial languages in Melkite Palestine in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Johannes Pahlitzsch;

The liturgy of the Melkite Patriarchs from 969 to 1300, Joseph Nasrallah;

Byzantium's place in the debate over Orientalism, Averil Cameron;

Index.

About this book we are told:

This volume brings together a set of fundamental contributions, many translated into English for this publication, along with an important introduction. Together these explore the role of Greek among Christian communities in the late antique and Byzantine East (late Roman Oriens), specifically in the areas outside of the immediate sway of Constantinople and imperial Asia Minor. The local identities based around indigenous eastern Christian languages (Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, etc.) and post-Chalcedonian doctrinal confessions (Miaphysite, Church of the East, Melkite, Maronite) were solidifying precisely as the Byzantine polity in the East was extinguished by the Arab conquests of the seventh century. In this multilayered cultural environment, Greek was a common social touchstone for all of these Christian communities, not only because of the shared Greek heritage of the early Church, but also because of the continued value of Greek theological, hagiographical, and liturgical writings. However, these interactions were dynamic and living, so that the Greek of the medieval Near East was itself transformed by such engagement with eastern Christian literature, appropriating new ideas and new texts into the Byzantine repertoire in the process.Contents:

Preface

Introduction: the social presence of Greek in Eastern Christianity, 200-1200 CE;