A recent publication from Ashgate looks set to begin filling a considerable gap in the science-religion debate:

Science and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Under the editorship of Daniel Buxhoeveden and Gayle Woloschak, this volume brings together numerous scholars reflecting on some of the most pressing questions today:

Contents: Preface; Part I Science and Orthodox

Christianity: Compatibility and Balance: Living with science: Orthodox

elders and saints of the 20th century, Daniel Buxhoeveden; Science and

the Cappadocians: Orthodoxy and science in the 4th century, Valerie

Karras; Divine action and the laws of nature: an Orthodox perspective on

miracles, Christopher Knight; Ecology, evolution and Bulgakov, Gayle

Woloschak. Part II Science and Orthodox Christianity: Limitations and

Problems: Science and reductionism, Thomas Mether; Limitations of

scientific knowledge and Orthodox religious experience, Daniel

Buxhoeveden; Discerning the spirit in creation: Orthodox Christianity

and environmental science, Bruce Foltz; Orthodox bioethics in the

encounter between science and religion, John Breck. Part III Science and

Orthodox Christianity: Selected Topics: The broad science-religion

dialogue: Maximus, Augustine, and others, Gayle Woloschak; Technology:

life and death, Gayle Woloschak; Apophaticism and political economy, C.

Clark Carlton; Towards an Orthodox philosophy of science, Thomas Mether;

Bibliography; Index.

I asked both the editors for an interview to discuss this book and the issues it addresses. Here are their thoughts:

AD: Tell us about both your backgrounds:

Daniel

Daniel: I received my BS from the State University of New York, Stony Brook with a major in philosophy and minor in physical anthropology; my MS and Ph.D. in biological anthropology from the University of Chicago; and a JD from Loyola University, New Orleans. My scientific specialty is the minicolumnar organization of the neocortex and I have researched differences between humans and nonhuman cortex as well as differences between controls and individuals with autism, Asperger's syndrome, Down syndrome, and schizophrenia in extant populations.

My focus in the last few years has been religion and science. I received a grant from the John Templeton Foundation and the Virginia Farah Foundation to pursue this topic in the Orthodox Church. I am director of the science and religion initiative at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. I began this endeavor some 6-7 years ago with about 8 faculty and now have over 30 faculty on a mailing list.

Gayle: I received my Ph.D. from the Medical College of Ohio in Toledo and did post-doctoral training at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. I worked at Argonne National Laboratory outside Chicago as a senior scientist, and then moved to Northwestern as a professor about ten years ago. I teach radiation oncology to residents, and nanotechnology and molecular biology to graduate students. I have a lab group of about fifteen people and enjoy my research in nanotechnology and radiation biology.

I also teach several science-religion courses at the Zygon Centre for Religion and Science at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago, and am associate director of the Centre. I am a member of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA and active in a number of groups within the Church in the US.

AD: How did you come to work together on this particular volume?

Daniel: One of the aims of the grants, especially from the Virginia Farah Foundation, was to complete a book on science and the Orthodox Church. I asked Gayle if she would work with me on this project since we have worked together since I first began my science and religion initiative. Gayle is probably the single most qualified Orthodox person in North America on the topic of science and religion and I was fortunate to have her help.

Gayle: Dan had a Templeton Grant to work on this, and I was a collaborator on his grant and we had agreed to do this book as part of the grant funding. Dan and I have known each other for at least five or six years now, and so collaboration was natural.

AD: For whom did you put together this volume--did you have a particular audience in mind?

Daniel: The primary audience would be scholars and academics. This was not aimed specifically for a lay audience. Having said this, the goal of the book is to engage the Orthodox community beginning with Orthodox scholars. The Orthodox Church lags behind the efforts of other Christians in the dialogue with science and this book is an attempt to turn this around.

Gayle: I think we were hoping for a scholarly audience of people who are interested in the interface of science and religion within the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox Church does not have as much dialogue on this issue as needed in the face of the many technological issues that are coming up. The book was part of a plan to engage Orthodox and other Christians in the discussion more intensely. These sorts of discussions will require an interdisciplinary approach and our goal was to try to bring different people with different backgrounds together for discussion.

AD: This book seems in many respects to be ground-breaking. Work on science

and religion has not often been done from an Eastern Christian perspective.

What areas especially remain under-explored?

Daniel: What I am hoping for is to stimulate interest in and discussion among the Orthodox community. The lay people may rightly be confused if they do not have a sense of where the Orthodox church stands on some important issues. I used the word ‘Church’ in the title rather than theology precisely because I think this is a Church issue and not one that needs to be addressed only by theologians and scholars, though they need to lead the way. Gayle would have a better grasp of what is lacking in the Orthodox Church in this regard than I would. However, I would say that the topic of biological evolution cannot be avoided. Another vital and under- explored area is neuroscience and the question of consciousness and brain. The latter topic is especially critical for theology. A more general but equally important theme that needs to be openly addressed is what is our approach to modern science (and technology)? Is it one of hostility, dialogue with mutual respect? Can science ever inform theology and vice versa? Is modern science fundamentally at odds with an Orthodox understanding of life as some claim? So I see both fundamental questions like this as well as specific issues that need to be addressed in an atmosphere of mutual respect that involves scientists, Church scholars, other academic disciplines, and clergy among others.

Gayle: It would be easy for me to come up with a huge laundry list here, but I think you can find Orthodox scholars who have written on many of the issues engaged by modern science. The broader issue is the need for discussion on these topics. Few problems can be resolved by a single scholar writing a single book or article. The hope is always that a work of scholarship elicits more discussion to help the Orthodox faithful gain a consensus on a given issue. I gave a workshop recently to a parish on stem-cell research, and I did a survey before and after the presentation. I was stunned at how much of a convergence of ideas there was after the presentation, mostly as a result of discussion that took place during and after the presentation. Within our parishes there is a huge need to engage many of the topics discussed in

Science and the Eastern Orthodox Church and others as well. We need to create space where these discussions can be done openly and honestly.

AD: Are there unique perspectives on science that Orthodoxy has to offer that may have been overlooked or are otherwise missing from Western Christian

discussions and treatments?

Daniel: I think so. Certainly work by people like

Alexei Nesteruk is a different approach that utilizes a definition of theology as knowledge of God rather than its more academic understanding. I think the emphasis on the experiential aspect of Orthodox experience of God may be different than many other Christian perspectives and actually remove a sense of conflict with science. This kind of approach (knowledge of God as experiential and hence ‘positive’ as opposed to speculative and rationalistic) is argued by a number of modern Greek theologians as well. Another persective is that historically there has not been the antagonism and problems with modern science that arose in the West.

Gayle: Because of my position at the Zygon Center, I am often asked to attend and speak at Lutheran Church conferences in bioethics, science and religion, and on other topics. There are some common grounds that can be found among Christians and perhaps all believers on particular issues--e.g., respect for the earth, love and caring for the other, respect for life, and others. Nevertheless, the Orthodox Church brings a unique perspective to these discussions. Among Christians, the Orthodox view is often highly respected as being well-grounded in the Fathers and Tradition of the Church. I often tease my Lutheran colleagues that we may get to the same place on particular issues after all but we will probably get there differently, calling to mind different teachings and perspectives than they would.

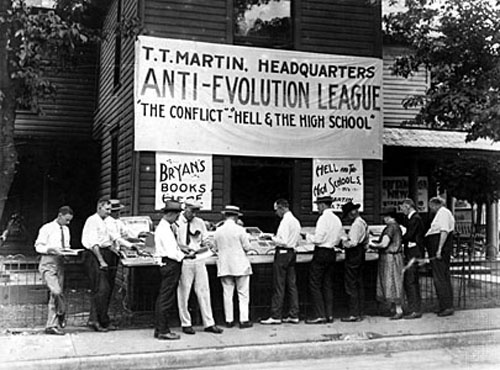

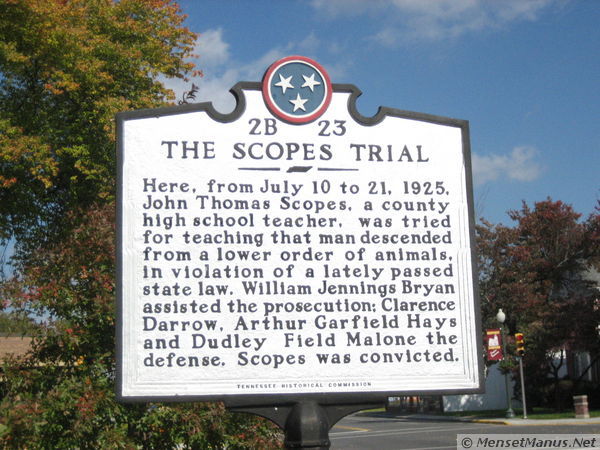

AD: In the US there is a debate now going on 80 years or more about whether

theories of evolution can or should be taught in school. What perspectives

does Orthodoxy bring to those debates?

Daniel: In high schools we teach the current models used in the sciences. My approach is that if biological evolution is a model in science then that is what we use. We do not make exceptions for those we do not like. The problem is multifaceted but includes a misunderstanding of what biological evolution is, what the evidence is, the nature of a model in science, what kind of knowledge scientific knowledge is, as well as the literal approaches to Genesis that seem unnecessary and un-Orthodox. Coming to Orthodoxy I found in general a much more open approach to evolution, to science, and an appreciation that Genesis is not a book that is concerned or focused on geology, biology, or physics.

Gayle: This question would take me a long time to answer. I wrote an article for

St. Vladimir's Theological Quarterly recently on the issue and some of the chapters in the book also touch on the matter. I do not believe that the Orthodox Church ever accepted a literal interpretation of Scripture and an acceptance of the Genesis 1 account of creation as literal would negate the many other creation accounts found in the Old Testament, including those in Genesis 2, Psalms, Job, and others. As a scientist I believe that the evidence for evolution is not refutable and therefore I can find no grounds as to why it would not be taught in schools. Evolution is the unifying model for all of biology, and without it nothing in biology makes sense (to paraphrase the evolutionary scholar and Orthodox Christian Theodosius Dobzhansky). Most of medicine uses evolution--we test drugs on chimpanzees and not on frogs because chimps are evolutionarily more related to us; thus rational drug design uses evolutionary tools and more.

AD: One area where Orthodoxy seems to have made a particular and manifest

mark recently is in the religion-ecology debate, led in no small part by the so-called Green Patriarch, His All-Holiness Bartholomew of Constantinople. What is unique about the Orthodox contributions to this debate? Who else is doing work in the area from an Orthodox perspectives.

Daniel: I just reviewed a new book by a host of Orthodox scholars on this topic. I was very impressed with the scope of discussion and look forward to the publication of this work. The best answer I can give to that is to take a look at

Science and the Eastern Orthodox Church. This is a topic that easily fits into an Orthodox ethos and at the same time Orthodoxy can rescue the ‘ecological movement’ from excesses like pantheism misanthropy.

Gayle: There is a large number of scholars working in this area, and you can find some of them in our book. I know that Fr. Deacon

John Chryssavgis and Bruce (Seraphim) Folz have been trying to complete a book edited from a conference on Orthodoxy and ecology held several years ago. The Orthodox Society of the Transfiguration has worked for many years to bring an ecological consciousness to the Orthodox Church. Many parishes have green activities including several that have gone to solar panels and other means of ecological awareness.

AD: It has almost become a truism that technology today far outstrips our moral reflection. That is, we can do things, but the question of whether we should do them remains unexplored or under-explored. Which issues in particular do you think Orthodoxy should be more deeply addressing in the twenty-first century?

Daniel: One of them may be transhumanism, the use of technological replacements for the human body. At the extreme some call for going beyond the human with the merging of biological aspects to machines. This mindset sees the body as weak and the machine as enduring and is also associated with attempts to prolong life indefinitely. The latter is also something we should examine: the notion of trying to prolong human life beyond the traditional norms. Another is the use of communication devices and their effects on loss of the personal. One writer described our age as one in which communication has increased immensely while 90% of what is being communicated is banal in nature. There is also the question of technology and privacy and the overall problem of how to fit our devices into a sacramental world view and personal life. Can it be done? Is there anything inherently wrong with our technological ‘progress’ or is it merely how it is used?

Gayle: I work in a medical school so perhaps I am most aware of technological issues in that context. I touched upon some of those in one of my chapters in

Science and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Overall I believe that issues of stem-cell research and in-vitro fertilization, questions of genetic selection of offspring, genetic testing of individuals: these are issues really at the front line of life today that need to be examined. As technology increases, the number of decisions in a person's life also increases. When there was no in-vitro fertilization, the childless couple could decide to adopt or not. Now it is not just a question of whether to adopt or not, but then do we have a baby by in-vitro fertilization, do we have surrogate parents, do we do genetic testing of our child, do we do genetic selection of our child, and what do we do with unused fertilized eggs? These are just a few of the complex issues that most priests are not trained to address. I highly support the development of parish teams that include the priest and other professionals (doctors, nurses, scientists, etc.) to provide advice and counsel on these matters.

AD: Some people automatically assume the truth of the caricature that "science" is always antithetical to "religion," the former being ostensibly objective and evidence-based, and the latter subjective and superstitious. How can Orthodoxy help to overcome this divide?

Daniel: There are maybe four general ways to view the science and religion interface. One of them is the conflict model. Historians now discard this model as having no sound historical basis. Rather it was derived from two influential but highly biased and inaccurate books written in the 19th century and is also known as the Draper-White conflict thesis. Atheist and agnostic scholars seem to agree that there is no inherent conflict here. That being said, too many lay people and academics hold this view. A recent study of scientists (physical, biological, and social) at elite universities found that 47% of them believed in God. On the one hand, this is far lower than the national average but on the other it does not show an across-the-board hostility. Education is the key, which is why I am involved in the science and religion dialogue. We need to talk about this so the perceived divide does not become wider. Inherent in this is a proper understanding of what scientific knowledge is. We have to move away from what atheist philosopher of science

Mary Midgley (and others), refer to as ‘imperial science.’ The key is that there is more than one form of knowing, one approach to reality, to what IS. The physical aspects of a Monet painting (the chemistry, oils, canvas, etc) are true as such but do not ‘explain’ the entirety of what the painting as a thing IS. Monet was not doing chemistry or physics: he was creating art. It depends on the question being asked: is this good art? How do we help prevent deterioration from the elements? The answer derives from different forms of knowledge. On the other hand, the physical attributes are hardly at war with the object as art--that would be silly. They help give rise to the art. We need perspective and balance.

Gayle:

Francisco Ayala, the winner of the Templeton Prize for Science and Religion two years ago and a Catholic priest and scientist, wrote that science is one way of knowing, but it is not the only way--we derive knowledge from many other sources including spiritual reflection, artistic expression, and others. To limit ourselves only to what is scientific limits us to the material dimension only. For Orthodox Christians, as humans we are spiritual and physical creatures both, undivided. I do not think this division between science and religion, which is the perception of much of the culture around us, is natural for humans, and certainly not natural for Orthodox. It is somehow a product of a limited way of looking at the world.

AD: Sum up for us the main themes and achievements of the book.

Daniel: The main theme is perhaps the fact that we have Orthodox scholars in North America who are willing to engage this topic. I envisioned this as only a start and hope to see follow up editions with other authors added. Most books of this kind in English are not only scarce but written by one author. I wanted to get multiple views so no one person dominates the discussion or attempts to speak for the Church at large. This is the beginning of what I hope will be a nationwide discussion. If the book helps move this along in anyway, it will have achieved its primary purpose.

Gayle:

Science and the Eastern Orthodox Church was the work of a group of Orthodox scholars who showed their tremendous commitment to the science-religion debate by their willingness to put their thoughts and ideas to words in a cohesive way. This was exciting for me personally. The quality of the scholars and the work that was done is truly amazing and it is a credit to their talents that the book was completed. I hope that this is the first of many such projects to engage discussion on science and religion together.