There is news emerging that the life of the emeritus bishop of Rome, Joseph Ratzinger, is moving peacefully towards its close. For someone who is almost 90, and who resigned three years ago because of increasing frailty, this story comes as no real surprise. Two years ago, on the anniversary of his resignation, I offered some thoughts here towards a preliminary assessment of his legacy as Roman pontiff. I abide by my judgment then that the most significant thing he did as pope was to issue Summorum Pontificum.

There is news emerging that the life of the emeritus bishop of Rome, Joseph Ratzinger, is moving peacefully towards its close. For someone who is almost 90, and who resigned three years ago because of increasing frailty, this story comes as no real surprise. Two years ago, on the anniversary of his resignation, I offered some thoughts here towards a preliminary assessment of his legacy as Roman pontiff. I abide by my judgment then that the most significant thing he did as pope was to issue Summorum Pontificum. However near or yet far off his death may be, it is clear that his written corpus will see no new additions, and so now is as good a time as any for a look back at just some of his books and their impact on Catholic-Orthodox relations and on issues of especial concern to Eastern Christians.

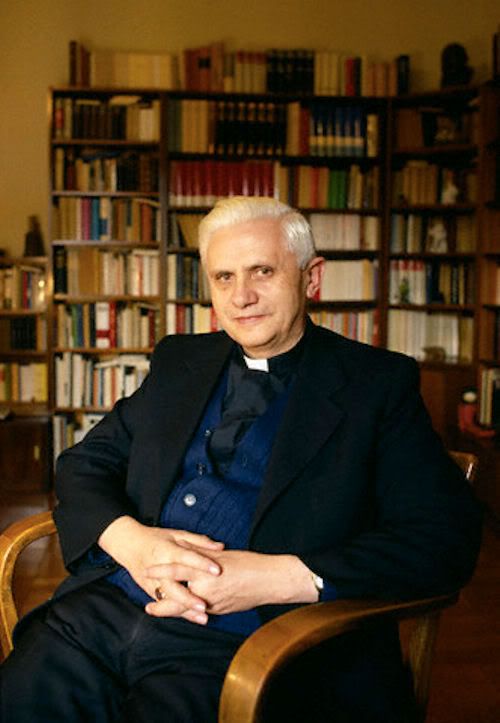

I think my first two introductions to his writings were of a personal nature. There was, first, his moving and deeply human homily (which I have often quoted on here) at the funeral Mass of his friend Hans Urs von Balthasar, reprinted in the collection edited by David Schindler, Hans Urs Von Balthasar: His Life and Work. This collection I read from my hospital bed in 1996 where I was immobilized for three months after being hit by a bus while riding my bike. It was, perhaps, my first introduction to a thinker who was not only subtle and scholarly, but also gracious, warm, and human--not at all the Panzerkardinal of the lurid and gratuitously unjust grotesques constructed by the mass media with the encouragement of not a few jejune Catholics who get their theology from the New York Times.

The next year, Ratzinger published the first (and, alas, the only) volume of his memoirs, Milestones, which rather hinted at being the first of at least two volumes. It stopped in 1977, the year Ratzinger was quickly vaulted into both the episcopacy and the college of cardinals--the last such appointment Pope Paul VI would make before his death the next year. (Had a second volume appeared, covering his Rome years as prefect of the CDF.....oh how the mind reels with thwarted excitement at the tales he could have told! Of course, some of his views from that time were candidly shared in his several book-length interviews, starting with the first and greatest bombshell given after a scant three years in the Roman

After a brief stint as archbishop of München und Freising in his native Bavaria, Ratzinger would be lured to Rome by his friend Pope John Paul II in 1982....and never be able to leave, though his desire to do so, especially as the 1990s ground on, was well known.

The year after Milestones appeared, 1998, I was in Rome at a conference at which Ratzinger was the keynote lecturer talking about his favored topic, the liturgy. In English his first treatment of this vital area came about in the 1981 translation, The Feast of Faith, a short little book more than worth its price for its preface and introduction alone, where he deals, as succinctly as anyone ever has, with the "relevance" of studying liturgy in a world full of political conflicts and social problems. It was the first of several studies about liturgy that would make their way into English and enrich my thinking on this most vital of topics.

In addition to liturgy (about which more presently), Ratzinger offered important clarifications and corrections as to how theology should be done in such books as The Nature and Mission of Theology. He was of course often not just criticized but attacked, often in the most adolescent way, not least by not a few of the preening members of the Catholic Theological Society of America who thought that Ratzinger's ideas of theology--unofficially expressed in this book, and more officially in CDF pronouncements such as Donum Veritatis, about which I have written here--were intolerable impositions and odious expressions of a libido dominandi when, of course, they were simply invitations to return to doing theology as it must always be done, viz., on its knees, as he was wont to say--as "praying theology." This, as Eastern Christians will at once recognize, is simply how the holy Fathers did theology, and to the extent that Ratzinger helped to re-orient theology, he performed a service at once theological and ecumenical. I found nothing whatsoever objectionable in such invitations as his, and indeed much that was inspirational.

Ratzinger has also, of course, been influential in shaping Catholic ecclesiology from Vatican II onward, as encapsulated in his little book Called to Communion, which is a helpful summary of the so-called eucharistic or communio ecclesiology whose recovery in both East and West in the last half-century has been the single greatest such development and has served to bring each closer to the other.

More than that, however, Ratzinger, more than any other figure in 20th-century Roman Catholicism, was the first and most sustained thinker--starting in a series of scholarly articles from the late 1960s--to focus on the importance of papal decentralization as seen through a recovery of the institution of the patriarchate within the otherwise bipartite structures of the Latin Church. He returned to these thoughts somewhat in at least one of his later book-length interviews, both of which were conducted by Peter Seewald.

And then.....and then there was of course his election in 2005 as bishop of Rome, and almost immediately (as in the insignia at his inauguration in April of that year) he gave signs of a return to an earlier, and more commonly recognized, tradition. He had written and spoken frankly during John Paul II's pontificate of his pronounced dis-ease with the cult of celebrity that had grown up around the papal office, and gave every sign of wanting this pared back. (He also gave clear evidence, I thought, of his own discomfort with the office, and I felt acutely sympathetic towards him as a fellow introverted academic happiest in his library. How often did I look at him and think of the Petrine conclusion to John's gospel when Christ says "when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go.")

A year later, he announced, rather abruptly and indirectly, that the title "Patriarch of the West" was being deleted from the list of titles in the Annuario Pontificio. There was much shock at this, and I spent considerable effort writing articles in a variety of places trying to reassure Orthodox Christians that this was a good thing--that it was the start of the re-structuring of the Latin Church, and the creation of regional patriarchates, that Ratzinger single-handedly had talked about creating for 40 years. Readers of my Orthodoxy and the Roman Papacy will be familiar with all these arguments in detail.

And then? Nothing. No further developments beyond a hastily cobbled together and badly translated statement from Cardinal Kasper trying to defuse the situation. There were no further developments--no new titles, no new offices, no newly created patriarchates of, say, North America, or francophone Africa, or Latin America. What seemed by every indication to be the beginning of a significant ecclesiastical re-structuring came to nothing, which I confess was an enormous disappointment at the loss of an opportunity to make arguably the most ecumenically significant changes the East could ask for.

Ratzinger did, however, go some distance towards the East in his earlier book, The Spirit of the Liturgy. There he also tried, however inadequately, to address one of the most acute crises in the Latin Church at and following Vatican II: its rampant and flagrant iconoclasm.

The book is not only a much-needed critical treatment of just some of the many disastrous developments in Latin liturgy over the last 50 years. It is also a frank acknowledgement that neither in the 20th century, nor really for any of the twelve centuries before that, has the Church in the West adequately or fully received the teaching of the seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 787, the one devoted to the defeat of Christian iconoclasm. Ratzinger rightly called for Nicaea II to be newly appropriated in the West--a development which, sadly, few seem inclined to undertake.

If his book continues to serve as a thorn in the side of Western Christians, prompting them to re-evaluate their iconoclasm, as Jeana Visel (almost alone) seems to be doing, then it will remain in my estimation the most lasting contribution of a most estimable scholar and gracious gentleman now in the sunset of his richly productive and long life. When that sad day comes and Joseph Ratzinger leaves the Church militant for, one hopes, the Church triumphant in heaven, may the Lord's judgment be swift and merciful: "Well done, good and faithful servant! Enter into the joy of your master."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Anonymous comments are never approved. Use your real name and say something intelligent.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.