Last week I posted a

review of Fr. Oliver's splendid new book. I had previously sent him some questions for an interview, and here are his replies.

AD: When we last talked on here,

it was about your book on Serapion of Thmuis. How, in the last two years, have

you moved from ancient Egyptian patristics to Turning to Tradition: Converts and the Making of an American Orthodox Church?

Was this a planned development or an unexpected move? What, if anything, links

the progress from the first book to the second?

OH: I admit that is a jump! Would it surprise you to know I published an

article on Anselm and one on Bonaventure during the interim (in addition to

articles on American Orthodoxy)? The

move was both planned and unplanned. Dr.

Lois Malcolm at Luther Seminary told our systematics class (and presumably she

tells each class this) that it is wise and helpful to have two periods of

church history from which to draw when developing one’s theology. That stuck with me and so I have always felt

it to be important to have a handle on some geographical and temporal location

in the early church together with a later period. I privately decided to one-up Lois’ class

challenge and committed to finding three periods, to triangulate my theology. It’s

been a slow go to develop the third (Byzantine theology of the eighth, ninth,

and tenth centuries, which is slowly coming to the fore and lies behind the

Anselm and Bonaventure articles and guides a current project in collaboration

with Brian Matz of Carroll College on the filioque

dispute of the ninth century—may we see that through!).

In

my case, I wanted to be grounded in patristic thought and at St. Vladimir’s, I

encountered Sarapion, who intrigued me, as he was a desert father, but also

clearly an astute, philosophical intellectual.

I also admitted that I had sympathy for him as a little known

saint—there’s something about a “dark horse.”

Anyhow, when I went to SLU, I fully intended to write a dissertation on

Sarapion. About a year-and-a-half into

my studies, though, I found American historical theology to be not only the

second area in which to ground my theology, but the area that interested me

more. I didn’t expect that. So, finding a second, modern period was

planned (because of that class at Luther) but finding it to be “American” and

finding that to be more interesting to me than fourth century Egypt was

unplanned. Up to that time, I had a

relatively generic view of Orthodox history in America. As I researched and wrote my

paper-turned-article on Nicholas Bjerring, the first convert priest in 1870,

however, I realized just how much Orthodox overlapped with theological

movements in America. I also realized

that many of the generalizations of that generic history needed to be

questioned. It was all downhill after

that. By that time, I had done so much

translation work on Sarapion (with encouragement from Fr. McLeod) that I

decided to finish that up and complete a manuscript, which I did. It took a little while for it to go through

the publication process, but it did. So,

I published a book on what would have become a dissertation and then completed

a dissertation and have now published that book.

I

should note that Cornelia Horn gave as good a pitch as any to get me to

re-prioritize my areas of research, and I’m thankful for working with her as

well, but American Orthodoxy is too fascinating to me. There is also the fact that Fr. John

Erickson, who was on my dissertation committee, and my advisor, Michael

McClymond, have an interest in American Christianity that is contagious.

So,

in the last few years I have found myself writing articles on American

Orthodoxy and completing this book. I’m

quite thankful to be where I’m at in terms of research and publications.

AD: In your introduction you use

several striking and revealing terms such as "ecclesiastical

restorationism" Could you elaborate a bit on that term for us?

OH: Sure. By using the phrase ecclesiastical restorationism,

I meant to highlight two things. First,

that what is going on here is something more than merely switching

denominations on the one hand (say, going from Lutheranism to

Presbyterianism). The converts were

doing more than denominational hopping.

They were operating within a restoration paradigm, seeking to restore,

or reconstitute, something.

The

second (and most important) thing I hope this phrase highlights is that the

converts in question were not simply looking for a past historical standard but

a past historical ecclesiastical standard—a past church that set Christian norms.

This is why tradition was such a concern. They were concerned not merely with a

tradition of ideas, but a tradition of a kind of religious existence. In fairness, of course, any restorationist

Christian movement will seek to reestablish the early church but in the case of

these converts, it went beyond that, with them looking for a “church” that

could be found to have existed early on and to have set the standards to which,

they believed, we are all to adhere.

That is to say, “church” was not a secondary or derivative concern, but

a primary one.

AD: You speak of the role of

theology in conversion. Is there one consistent role for theology? At risk of

generalization, could one inquire as to whether theology plays a major role

positively--coming to embrace Orthodox theology for its own sake as the

fullness of truth--or is the role of theology largely "negative" for

converts insofar as Orthodoxy represents what my former tradition is not

(liberal, pro-gay, etc)? Or perhaps it's a mixture of both?

OH: This is an interesting

question.

When I began looking at

theology as a factor, I had primarily the work of Lewis Rambo and

Amy Slagle in

mind.

For Rambo (and for Scot McKnight

who has adopted Rambo’s system), theology sets patterns of behavior.

I didn’t think that was really the primary

role of theology in these conversion narratives, at least not initially.

Additionally, Slagle’s study had noted

theological factors but it wasn’t her task to assess them.

I decided to investigate what theological

conclusions were driving

the conversion

process and whether those conclusions fit within any larger trend(s) within

American Christianity.

Interestingly,

what I found could be argued to have brought me back full circle, inasmuch as three

of the four converts studied pioneered theological norms for intra-Christian

conversion to Orthodoxy.

That is to say,

they promoted their way of looking at things and it guided many into the

Orthodox Church.

I

say all this by way of preface, because what I found was that theology was,

indeed, a “mix.” It could operate both

positively or negatively, in the ways you describe. I think the primary way in which it

functioned as “positive” was that the converts were making legitimate

conclusions to the best of their ability.

If we deny that, then I think we end up down-playing what was motivating

them at their core. That said, this positive

use was very much wedded to a negative use at times. You see that in Toth with his polemics, which

could be quite vehement. You see this in

Morgan and Berry on the issue of race and in Berry’s case in seeking something

that isn’t too tied to “this world.” You

see it in Gillquist in his disgust with “parachurch.” Others within the EOC who converted with

Gillquist and are mentioned likewise had some negative motivations. These negative motivations were important,

but the motivations in and of themselves did not create the conclusions, for

the converts could have chosen any other number of possible solutions than

Orthodox Christianity.

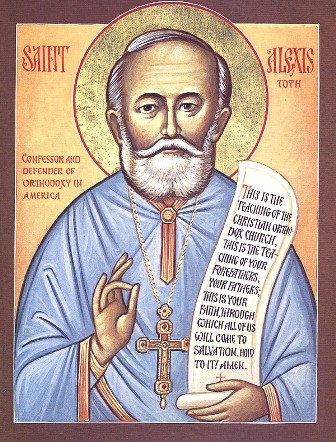

AD: Your chapter on Alexis Toth

also discusses Josaphat Kuntsevych, and it has long been a question of mine as

to how each side should regard the other's saints, especially as one works

towards unity. To put it crudely, one church's heretic is another church's

hero. Toth, of course, was a former Eastern Catholic who became Orthodox and

was canonized by the OCA while Kuntsevych went the opposite route, ending up a

canonized martyr in the Ukrainian and Roman Catholic Churches. What are your

thoughts on these competing martyrologies? How should we regard them today--as

embarrassing emblems of nasty practices from the past we think we would never

do again today? Or should their holiness be considered primarily on its own

more individual and personal terms without regard to the ecclesial politics?

(This issue came up in the Byzantine-Oriental dialogues where both liturgical

traditions have canonized saints and anathematized heretics that are the direct

opposite of each other, and neither side seems to know what to do about that

since they do not want to simply abandon liturgical texts that have been prayed

for centuries.)

AD: Your chapter on Alexis Toth

also discusses Josaphat Kuntsevych, and it has long been a question of mine as

to how each side should regard the other's saints, especially as one works

towards unity. To put it crudely, one church's heretic is another church's

hero. Toth, of course, was a former Eastern Catholic who became Orthodox and

was canonized by the OCA while Kuntsevych went the opposite route, ending up a

canonized martyr in the Ukrainian and Roman Catholic Churches. What are your

thoughts on these competing martyrologies? How should we regard them today--as

embarrassing emblems of nasty practices from the past we think we would never

do again today? Or should their holiness be considered primarily on its own

more individual and personal terms without regard to the ecclesial politics?

(This issue came up in the Byzantine-Oriental dialogues where both liturgical

traditions have canonized saints and anathematized heretics that are the direct

opposite of each other, and neither side seems to know what to do about that

since they do not want to simply abandon liturgical texts that have been prayed

for centuries.)

OH: Oh, wow. This is a tough one and one I will admit not

having thought about nearly as much as I probably should, even though I first

encountered this in a real way at seminary, when Dr. Bouteneff asked us the

same question in a class looking at Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox

relations. So, I can only tell you where

I’m at currently, which may not be my mature thought as I give this more

time.

I

would say that what makes this question seem difficult is our sinful desire to

hold grudges and identify with an imagined past. It seems to be easy to identify with our own

church brothers and sisters who were wronged in the past and then to retain the

accusation of abuse against the contemporary expression of the opposing

religious body. One might claim this is

a “sacramental” aspect to “church.” This

could be especially so in the case of Orthodox and Catholics. Something like: “My church is the body of Christ and

therefore I am mystically present with the past abused persons when I go to

liturgy/mass and therefore those past abuses are still meaningful and real.” At other times, it’s much less profound and

is simply a way of attacking the church you do not belong to simply because it

doesn’t agree with your church.

However

it is expressed, it seems to me that what is needed a reconfiguration based on

the fact that the Church is, indeed, the Body of Christ. If I believe my church is the Church (or at

least part of it) then I should see the past martyrs as being able to exist at

a level in which they can say “Father forgive them, for they know not what they

do.” This perspective should then be

combined with humility, such that we no longer think it pertains to us to

continue the violence (even if by way of rhetoric). If these are combined, we can then become

open to the fact that each church has canonized people who helped people

against abuse from the other side. That

is, we will realize our side sinned too.

Our side also helped create tensions and violence.

So,

to return to your examples: a faithful Roman Catholic should be able to say

that Toth was right to oppose the prejudice he encountered from Western Catholics

and a faithful Orthodox Christian should be able to say Josef Kuntsevych’s

murder was wrong, as were the subsequent exaggerations later told to “justify”

his murder. At the same time, each side

should hope that in a reunited church, a former Roman Catholic could say Toth’s

faith is now dogmatically acceptable (even if he himself was mistaken at times)

and a former Eastern Orthodox could say Kuntsevych’s faith is dogmatically

acceptable (even if he was mistaken at times).

Their faiths would be seen as

reunited. So, in that context, I really

don’t see the problem for canonizing both men.

In fact, I think reunion would require that both remain canonized. For a real, lasting peace never ignores the

difficulties, but reconciles them.

AD: I'm struck by the very

different ways in with Catholic and Orthodox immigrants in the last century

adjusted to the American context. Archbishop Ireland seems to be a paragon of

the Catholic attempt to prove, as strenuously as possible, that Catholics were

just like Americans--they spoke English, they were patriotic, they worked hard,

they tried to blend in; but Orthodox seem more content to have retained

indigenous languages and practices and more comfortable, perhaps, appearing as "exotic."

And yet, the main burden of your book is in showing just how very much Orthodox

did strive to become American through, as you aptly put it, the very American

"anti-traditional tradition." Tell us a bit more about what you mean

by that phrase.

OH: Yes, well, that gets at the

central irony running through this book.

Here you have this faith that many Americans would still categorize as

“exotic,” that has received many converts who have operated according to a very

American pattern, and on the basis of that American pattern have, in turn,

sought to evangelize other Americans.

That American pattern is one of anti-tradition (which could be called an

anti-traditional tradition). America has

a long history of religious mavericks who emphasize a part of their previously

received tradition in order to create something new. This has led to an increasingly diversified

and complex religious scene.

Restorationist movements embody this anti-traditional tradition by

emphasizing aspects of what they had received in order to recreate what had

once allegedly existed prior to that tradition that was given to them. So, it is “anti-tradition” in trying to

by-pass the received tradition but a “tradition” nonetheless by virtue of being

an ongoing way of doing religion in America.

One restoration bequeaths another.

What has happened in the case of many American Orthodox converts,

especially those I examined in my study, was that their very desire to find

tradition was undertaken in a manner that represented the anti-tradition tradition.

What

is more, these converts then used this approach to lead and/or attract other

converts. This is important to note

because some have taken such actions by new converts as simply perpetuating

Orthodoxy’s “defensiveness” in the face of American culture when, in fact, it

is evidence of engaging American pluralism.

One sees this in the case of Gillquist, for instance when he went on to

encourage other Christians to join the Orthodox Church by arguing the Orthodox

Church exists not merely as a non-denominational church but as a

pre-denominational church. It also

becomes a way of trying to present the Orthodox Church to America in a way that

Americans could appreciate it.

AD: In your discussion about the

reception of many former Evangelical Orthodox into the Antiochian Archdiocese,

it occurred to me that in some clear ways Met. Philip is precisely an

embodiment of your 'anti-traditional tradition," yes? I'm thinking here of

his handling of the Joseph Allen affair as well as his performing a

"mass" ordination for the EO clergy in one liturgy. Is that a fair

assessment of him?

OH:

Hmmm.

Interesting that you should ask this.

Not long after the book came out, a colleague and friend emailed me and

wrote that Metropolitan Philip came off looking more like a lone ranger than

this friend had previously thought.

I

should point out that Metropolitan Philip was not a focus of my study.

He did, however, play significant roles in

the conversions of Gillquist and the most of the former Evangelical Orthodox

Church and so he appeared with some frequency in the last two chapters of this

work.

He was connected to controversial

decisions that affected that group of converts, including that of their

ordinations and the remarriage of Fr. Joseph Allen, which you mention.

And, to be fair, he performed other actions

surrounding those decisions that were (and are) controversial in themselves and

this doesn’t even touch on Ben Lomond and fallout from that.

So, I can see how one might wonder if

Metropolitan Philip doesn’t represent the anti-traditional tradition, but I

would argue he does not fit the anti-traditional tradition as I set it out in

my narrative.

Whatever one might think

of his actions at times, he has not, from the sources I consulted, sought to

recover and reestablish a previous norm.

He may be a religious maverick, but he did not exhibit the intention to

reestablish a previous norm by establishing a new church or some larger church reform.

Indeed, the only common denominator I saw was

himself.

I suppose if one were to

broaden anti-traditional tradition far enough, he would fit, but then the

phrase would merely be a synonym for a religious maverick of any kind whereas I

wanted to highlight the founding of new denominations, religions, or reform

efforts.

Perhaps someday someone will

study his legacy, for all its complexities.

When that day arrives, I would encourage that scholar to consult the

sources I did in addition to other sources that are relevant and to seek to be

as unpartisan as possible, allowing the sources to speak for themselves.

AD: Your work shows, as you sum

up at the end (p.156) that many converts "prioritized an earlier

expression of Christianity and have identified the Orthodox Churches as

continuations of that earlier church." This gets at something I've been

thinking about more and more over the past year--and have discussed in my

reviews of the new collection, Orthodox Constructions of the West: how many

Eastern Christians (and in a different direction, but with similar methods,

many "traditionalist" Roman Catholics also) appropriate history. I've

heard it said that few of us read history on its own terms. Instead we

"plunder it for present political purposes." Do you think that's

generally true?

OH: That’s a great question

because suspect there will be Orthodox who are not yet prepared to allow the

historical evidence to be what it is but will believe that somehow I must have

slanted it so that things did not look as neat and tidy (and triumphalistic) as

might be found in books such as

Orthodox

America, 1794-1776 or

Becoming Orthodox. What I would counter with

is that we need to distinguish between plundering for our own purposes and

investigating to address current concerns.

One can cherry pick any period of history to “prove” nearly anything but

that is different from saying, “here is a topic that is important to us

today—what is its history, its back story and what can we learn from this”?

AD: Following this, have you set

out, or have other especially Orthodox historians set out, any basic

hermeneutical and historiographical guidelines on reading and writing about

church history? It's often seemed to me that some guidelines or ground-rules

like that would be useful in trying to talk about (and defuse the tensions surrounding)

controverted issues like, say, the Fourth Crusade or the Union of Brest and

similar issues.

OH:

You’re determined to turn this interview into

a book project of its own!

I actually

think that what is eventually needed is an Orthodox philosophy/theology of

history.

I actually have that as a long

range goal, sometime later in my career.

I’m not even close to that yet, but I suppose there are a few things I

could say.

I have outlined what I think

historical theology means (see attached

PDF).

I think the most important

element is the ascetic—the effort to remain dispassionate as one researches and

studies.

This is not easy, for any

number of reasons.

One might already

have a predetermined outcome one wants.

For

instance, I suspect this happens at times when we

want to canonize a particular person or particular kind of

person.

One might also be cherry picking

in order to defend a particular point of view.

This is an extreme version of the predetermined outcome.

Alternatively, one might simply be too

colored by one’s political or ecclesiastical allegiance.

Here, the historian may be looking at all the

evidence but the way in which it is weighed might seem questionable.

We all have perspective and that shouldn’t be

denied but I think the biggest lesson we need to learn is to go into historical

inquiry as an act of disciplining the soul and achieving dispassion.

It may be a never ending goal, but must be

our goal nonetheless, especially those of us who would ground dispassion in

theosis, which comes through Christ.

AD: Sum up your hopes for this

book:

OH: I have several hopes for this

book. First, I hope it provides scholars

a way to assess many Orthodox conversions, if not the majority of them. As a by-product, I think my thesis could be

applied to analogous situations within the church, as you suggested by asking

about Metropolitan Philip. It didn’t

work in his case, but maybe it could still apply in others. Second, I hope this provides scholars,

Orthodox clergy, and Orthodox laity with a more realistic view of some

important converts and convert movements.

Orthodox have developed a fair amount of mythology surrounding Orthodox

converts, a mythology that has often been wedded to triumphalism (talk about a

lack of dispassion!). This work clearly

breaks through that and in that way, I hope it can serve as an example of the

kind of historical inquiry Orthodoxy in America needs (whether internally, from

Orthodox such as myself, or externally).

AD: What projects do you have on

the go now? What will the next book likely be?

OH: In true fashion for one who could simultaneously

work on Sarapion and American Orthodox converts, I have three projects in

progress.

First, I am collaborating with my

friend and colleague Brian Matz on translations of texts from the ninth century

filioque dispute.

We hope to have a manuscript that we could

submit a year from now.

Ed Sciecienski

mentioned our work in his book, but Brian and I got distracted by our other

projects, so it will be nice to return to this and publish it.

Second, I am also working on a

project that develops a virtue ethic from iconography. This work is intended not simply as an academic

piece, but as something that will be easily accessible to clergy and interested

laity. I am not sure how soon I will

have something to a publisher with this project. It will depend on what this spring and summer

bring.

A third project I am working on

is more in-depth than the first two. It

builds from my convert book, taking up the idea of engaging American

pluralism. This project will be an

exploration of American Orthodox engagement with religious freedom. I believe this is a much needed area of

exploration and in the conclusion I will directly engage some Orthodox

political theology, and argue for an Orthodox-informed “Christian

secularism.” So, if I hope the first two

will be to publishers within a year or so, this one will likely take a couple

of years just to get into (rough) manuscript form. This one might take a little while but I hope

it will be worth it.