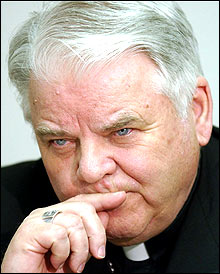

The second reason that D'Arcy was such a rare gift to the Church in our time was his track record in dealing with sexual abuse both in his native Boston and later in northern Indiana. As D'Arcy said to me last year, when he was a priest, and later auxiliary bishop, in Boston, he was nicknamed "D'Arcy the hatchet man" because he spent a good deal of his time rooting out seminarians and priests whose flawed characters made them unsuitable to exercise pastoral ministry.

Though D'Arcy didn't want to talk about it, the reason he was sent to be bishop in Ft. Wayne-South Bend, after spending his whole priestly and episcopal ministry in his native Boston, is very widely thought to have been a result of his unwillingness to keep silent over sexually abusive priests. (Phil Lawler's depressing and damning book The Faithful Departed: The Collapse of Boston's Catholic Culture is one of several sources that documents D'Arcy's courageous, commendable, and sadly rare stance.) D'Arcy put into print a number of letters that strongly suggested to his superior, the disgraced and disgraceful Bernard Cardinal Law, not to sweep the problem of predatory priests like John Geoghan under the carpet or shuffle him to another parish. Law ignored the warnings and, being a power-broker at the time (1985) in the Vatican under a pope who himself did not want to deal with the problem of abuse, seems to have fallen back on the time-tested ploy of promoveatur ut amoveatur. Thus D'Arcy was "promoted" to his own see hundreds of miles away and a few weeks before his mother died, enabling Law to go back to sticking his fingers in his ears and closing his eyes to a problem that would come back to haunt him spectacularly in 2002 and do such massive damage to the Church that it has still not recovered; the credibility of the bishops will take longer still to recover. Would that more of them had followed D'Arcy's example.

While we know that mentally and physically many abuse victims are simply shattered by the experience, what happens spiritually to those abused by priests and other leaders? Released last summer is a book that nobody wishes ever needed writing. It treats precisely this question: Susan Shooter, How Survivors of Abuse Relate to God: The Authentic Spirituality of the Annihilated Soul (Ashgate, 2012), 210pp.

About this book the publisher tells us:

Grappling with theological issues raised by abuse, this book argues that the Church should be challenged, and ministered to, by survivors. Paying careful attention to her interviews with Christian women survivors, Shooter finds that through painful experiences of transformation they have surprisingly become potential agents of transformation for others. Shooter brings the survivors' narratives into dialogue with the story of Job and with medieval mystic Marguerite Porete's spirituality of 'annihilation'. Culminating in an engagement with contemporary feminist theology concerning power and powerlessness, there emerges a set of principles for authentic community spirituality which crosses boundaries with God, supports appropriate human boundaries and, crucially, listens attentively. Appealing to Church leaders, students, practitioners and practical theologians, this book offers a creative and ethical theological enquiry as well as some spiritual anchor points for survivors.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Anonymous comments are never approved. Use your real name and say something intelligent.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.